The two-flat has been a stepping stone to the middle class and a source of affordable housing for more than a century. But for how much longer?

It’s been called a “workingman’s palace.” The humble two-flat is often named as one of Chicagoans favorite things about their hometown—along with hot jazz, Italian beef, and apartment back porches.

“It is Chicago’s answer to the Brooklyn brownstone, the Georgetown row house,” writes Chicago Magazine. With one very important caveat: The Chicago two-flat remains affordable, “still performing the duty to which it was first called in the early 20th century—that is, serving as both shelter and source of rental income for striving families moving up from cramped quarters.”

The two-flat was built en masse and on “spec” by and for the large immigrant communities of Chicago at the turn of the twentieth century, according to WBEZ.

Frank Stuchal was one of those immigrants, and the two-flat was his route to the middle class. According to WBEZ’s research, in 1900 the 24-year old Stuchal rented an apartment at W. 23rd Street and South Spaulding Avenue with his two sisters. In 1920 he and his wife owned a two-flat, half of which they rented out to a German family. And by 1930 he and his wife were raising their son in a bungalow they owned in the southwest suburb of Berwyn.

Buying the two-flat was a key stepping stone to the middle class for Stuchal and his family, and a source of affordable housing for working families. The same is true today. In 2015, units in the ubiquitous two-flats made up 27 percent of Chicago’s housing stock and an even larger share of its rental stock. Nationally, too, these smaller buildings are an important segment of the rental stock. And for lower-income renters, they are critical. A new report by Enterprise shows that average rents in buildings with 2-to-4 units are lower than for any other sized rental property. Because of this, 2-to-4 unit buildings are more likely to serve the lowest-income renter households than other sized buildings.

However, their future is in question.

The Decline of the Two-Flat

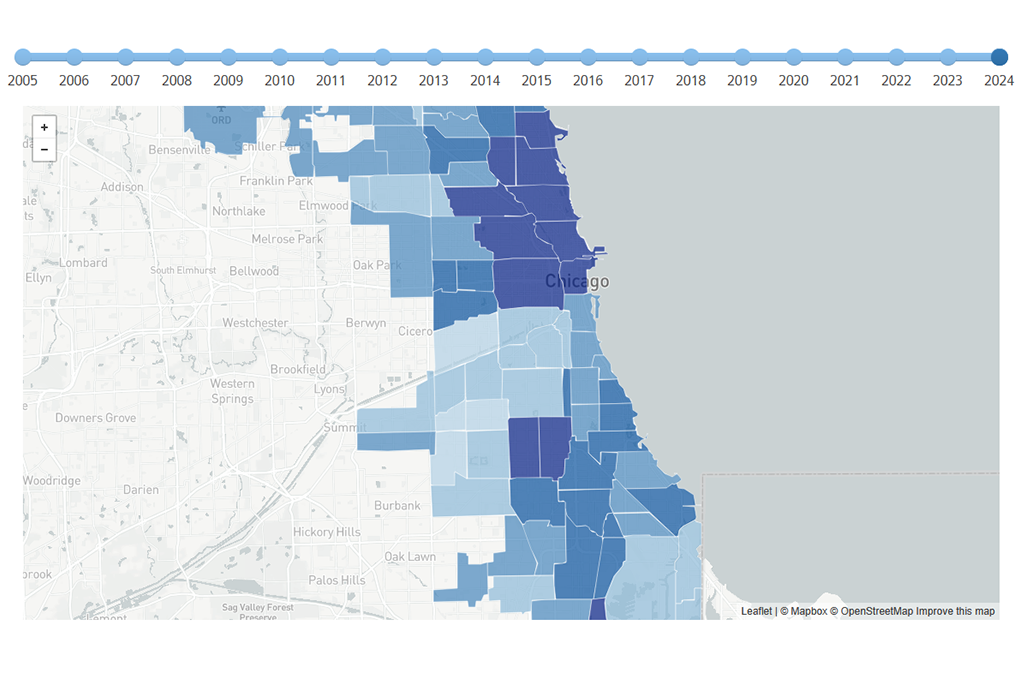

As our new report shows, the stock of 2-to-4 unit buildings is declining quickly, and that’s bad news for affordable rentals. In 2011, there were 301,461 rental units in 2-to-4 unit buildings in Cook County. In 2015, that was down to 279,704.

In neighborhoods ranging from Avondale to Humboldt Park to North Lawndale to Bridgeport, 2-to-4 unit buildings make up more than one-half of the housing stock, and their disappearance raises short- and long-term concerns about the stock of affordable housing.

Several forces are at work in this decline.

“In many Chicago neighborhoods with strong real estate markets, we have seen a growing demand for single-family homes,” says Geoff Smith, IHS’s executive director. “Unfortunately, these areas also have a small supply of single-family homes and very little vacant land for new development.”

As a result, he says, 2-to-4 unit buildings in these areas often are often converted to single-family homes or torn down to make way for new, high-cost single-family homes. This reduces the supply of rental housing in these high-demand neighborhoods and puts more pressure on the existing rental stock.

Two-flats in weaker markets face a different challenge: they were hit hard by the foreclosure crisis. Many of these mom and pop landlords simply couldn’t hold out. Nationwide, writes Allan Mallach in a Federal Reserve Bank of Boston publication, “fewer than half of the owners of two-to-four-unit family properties made an operating profit from their rentals.” That makes it hard to withstand any upheaval. As our data show, between 2005 and 2011, nearly one-third of the apartments in 2-to-4-unit buildings in Cook County’s low-income communities were affected by a foreclosure filing.

The loss of these buildings is alarming to Stacie Young, director of The Preservation Compact in Chicago. When we talked to her last fall, she was watching the loss of two-flats with concern.

“Brick two-flats had never suffered before,” she said of the impact of the recession on this stock. “It’s a critical stock and you create a newly distressed part of the housing stock that has never been distressed before.”

How to Preserve the Homes

One idea to preserve this critical stock is to better support the families that own two-flats with more resources and attention, and possibly federal and local government supports. “Privately-owned small rental properties fall between the housing policy cracks,” write Mallach. “Federal housing programs for the most part ignore them. The federal government has not had a program targeted at small rental properties since the end of the Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Rental Rehabilitation program in 1990.”

But unlike owners of larger buildings, according to advocates like Young, these working-class owners have little time or clout to talk policy change.

“These owners are busy fixing toilets, not lobbying Congress,” says Young.

Local programs are also scarce, says Mallach. “Few cities feel any sense of responsibility to help maintain or replace their stock of modest, affordable rental properties as they age,” he writes.

Young and her team at the Preservation Compact are stepping in to help. The Preservation Compact spearheaded a $26 million loan pool for responsible investors who want to redevelop 1-to-4 unit buildings as affordable rentals. Thousands of these distressed buildings sat vacant following the crash. Located in very weak neighborhoods with little or no homebuyer demand, these eyesores dragged down entire blocks. Rehabbing these buildings for use as rental housing can jumpstart revitalization, but traditionally banks have not readily made loans to investors for these buildings.

Launched by Community Investment Corporation (CIC) in 2014, the pool is now being expanded to meet demand. To augment this activity, CIC, Chicago Community Loan Fund, and Neighborhood Housing Services Chicago partnered to transform a $5 million grant from JPMorgan Chase into nearly $41 million to acquire and improve 600 units in buildings with one to four units. Formerly vacant buildings acquired and rehabbed by investor-owners now provide affordable rental housing for families in addition to adding stability and value to their blocks. Owner-occupants who received loans are able to stay in their homes as a result of financing otherwise unavailable. These programs help bring more one-to-four-unit rental buildings back onto the market in Cook County.

“As two-flats are lost in both strong and distressed markets, cities like Chicago lose a critical portion of their low-cost rental housing stock that will be difficult, if not impossible, to replace,” says Smith. “Therefore, strategies focused on preserving this stock are essential to any effort to provide affordable rental housing.”