Every day 10,000 Americans celebrate their 65th birthdays. That has been the case since 2011 and will be the case until 2030, according to Pew Research Center. At that point, nearly one in five Americans will be 65 or older.

How will the housing market respond as these Baby Boomers enter old age en masse? Seniors will likely need housing that is adapted to their needs with universal design features. They will need more supports as they age in communities with limited transit options.

And they will also need homes that are affordable and easily maintained.

The Fastest Graying Metro Areas

The metro areas with the oldest populations—outside the retirement havens of Miami and Tampa—tend to be in former industrial cities like Pittsburgh (ranked oldest in 2012), Buffalo (third out of 50 metropolitan statistical areas), and Cleveland (fifth). But not all of America’s most rapidly aging cities are in Florida and the Rust Belt. Even cities that draw millennials, such as New York (15th) or San Francisco (17th), are on the list of graying metros. One reason for the latter, Joel Kotkin writes, is that “these choice places are expensive to move into, so getting there some decades ago is a big plus. As the entrenched populations age, these places may become far more geriatric than commonly assumed.”

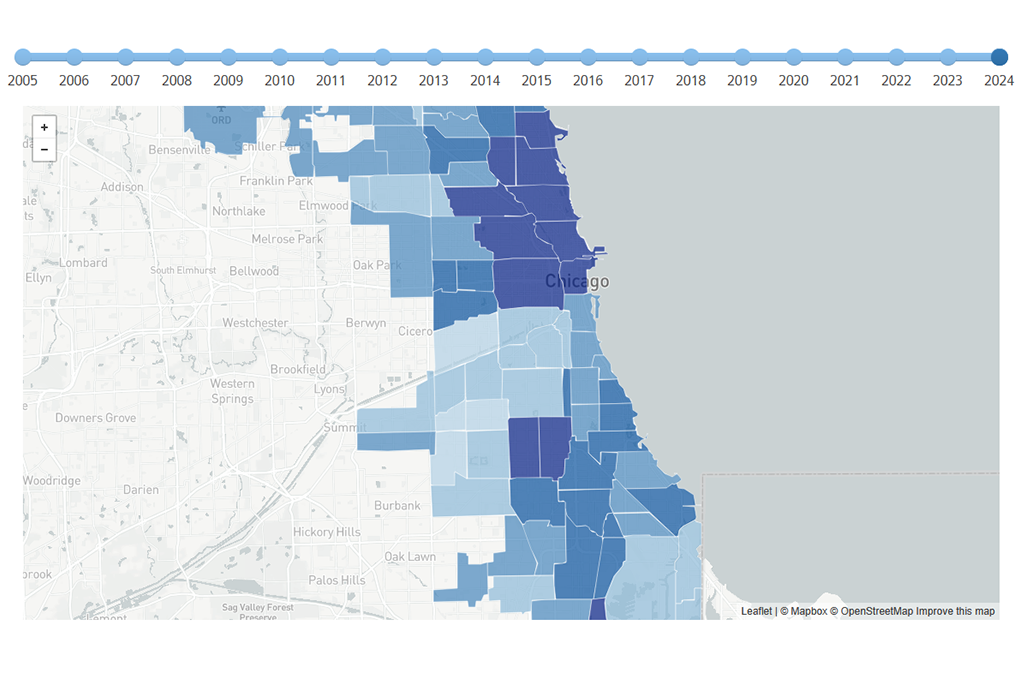

In Chicago (31st), older adults have been making up a growing share of the population. In Cook County, renters over age 55 accounted for 26 percent of all renter households in 2014 compared to 25.1 percent in 2007. In the Chicago region, the aging population is particularly acute in smaller, wealthier suburbs, according to a 2011 Crain's report. In these areas— Mettawa, Northfield, Oak Brook, Burr Ridge, Olympia Fields, and Palos Heights—55- to 64-year-olds make up 16-20 percent of the population, as opposed to a median of 11 percent in the Chicago area.

Financial Burdens on the Rise

But residents are aging across all neighborhoods and all income levels. During the past few years, severe housing cost burdens have shrunk slightly for most homeowners—except those 75 and older, notes the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University (JCHS). Meanwhile, JCHS projects that the number of households headed by someone aged 65 or older will increase by 66 percent, to more than 50 million by 2035.

More seniors are renting too, whether by choice or necessity, and nearly 2 million are burdened by the costs. From 2005 to 2014, the number of seniors paying more than one-half of their income for rent rose 34 percent to 1.8 million, according to the Make Room campaign. Many are also carrying a new form of debt, their grandchildren’s college tuitions.

The growing financial limitations can leave seniors without a desirable or safe place to live. Affordable rental housing for seniors is becoming scarce as economic pressures point developers to higher-return projects. Seniors in an affordable apartment complex in Chicago’s Lakeview community faced eviction last spring when the owner, Presbyterian Homes, claimed it could not renovate and support the subsidized apartments. The Chicago Housing Authority stepped in to save the building.

New Models for Aging Communities

The vast majority of people ages 65 and older—87 percent—want to "age in place" in their current homes and communities. But many homes are not equipped to meet seniors’ changing needs. In some cases, small or large modifications can provide a more affordable alternative to a big move. Recent research supports "universal design"—permanent features appropriate for residents of all ages that do not carry a stigma of being only for the elderly. Doorways wide enough for wheelchairs, side-by-side refrigerators and freezers, and light switches by entrances also fit the bill.

But efforts to modify the home are only one step and may not be appropriate for all older adults. For some, continuing to live at home is socially isolating in communities that were built around the cars or otherwise have limited access to transit, which can lead to depression and poor health. Communities themselves must adapt to allow the growing population of seniors to have options in choosing where to age.

New models of communal long-term care facilities are arising in response to the growing need. The Green House Project, for one, operates about 200 long-term care homes around the country, each housing about 10 people only. The organization’s goal is to create living spaces as close in design and function to regular private homes as possible. Although the cost is similar to a nursing home, some Green Houses are financed with New Market Housing Tax Credits or other programs that serve low-income seniors.

A less expensive alternative is a residential care home. These small sites blend into the surrounding neighborhoods. No skilled medical help is provided, but aides assist a small number of residents with meals and other basic needs.

Other options include rezoning the suburbs for more “accessory dwelling units,” detached small homes on the lot of larger homes, which allow seniors to live affordably near family. Sedona, one of the least affordable cities for housing in Arizona, approved an accessory dwelling unit ordinance in 2010. Several other cities have followed suit.

Finally, there is multigenerational living—except not with your own family but with strangers. At the nonprofit Pat Crowley House in Chicago, seniors pay 80 percent of their incomes for private bedrooms, food, and toiletries in a house they share with younger adults and college students. The younger roommates stay there rent-free, but help clean and cook for the older residents.

These innovative, affordable senior living options are growing—but not as quickly as the senior population is. Through modifications to the existing housing stock and the creation of new communal models, communities everywhere will have to adjust to the changing demographics—and soon.

Photo/Carolien Dekeersmaeker