After two years of construction, Chicago’s new 606 Trail opened to a flood of joggers, bikers, dogs, and strollers in early June.

Once an abandoned railroad line littered with debris and even an old piano, the trail stretches 2.7 miles through the city’s West Side. Four parks (two more are coming) extend from the elevated trail, and wide access ramps connect the walkway to the street below. It has been heralded as a landmark public space in neighborhoods where Chicagoans live, work, and play.

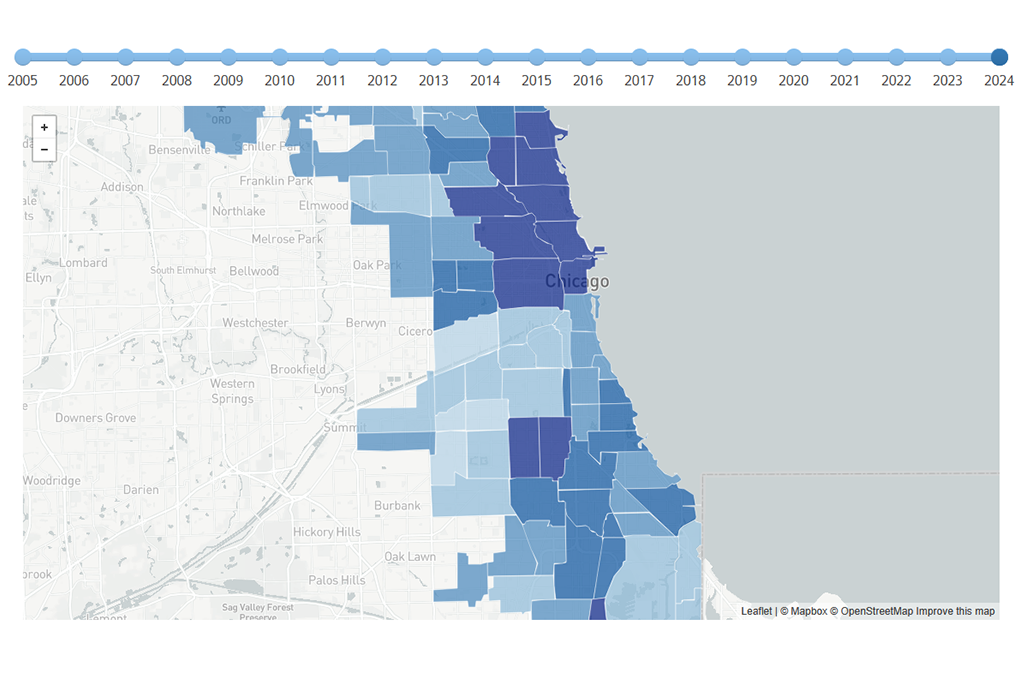

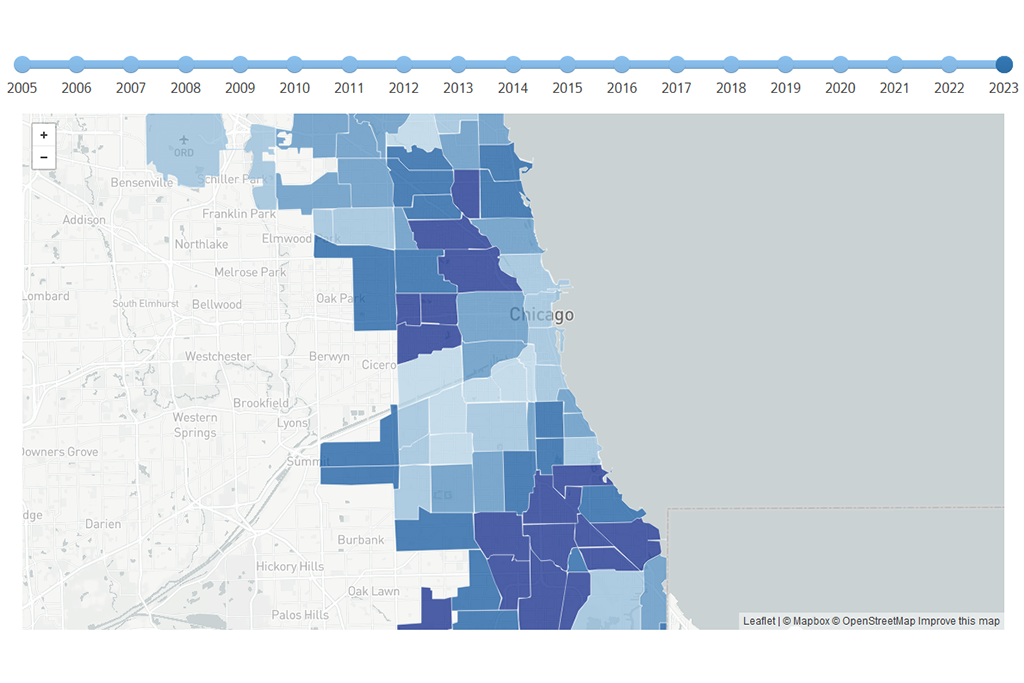

But while the trail brings potential for redevelopment in areas hit hard by the recession, it has the potential to accelerate the displacement of lower- and moderate-income residents in historically Latino neighborhoods. The grass hasn’t fully sprouted and garbage cans have yet to be installed, but the question of whether the 606 will be a trail that connects the West Side to the rest of the city, or pushes the residents who built the neighborhoods farther afield, remains to be seen.

Will the 606 Push Out Residents?

The 606 Trail is often compared to New York City’s High Line, another old rail line transformed into a public walkway and park. Before construction, housing prices around the park were 8 percent below the overall median for Manhattan. By 2011, they had increased 103 percent, according to The New York City Economic Development Corporation, forcing out residents and long-standing businesses. Today, about 5 million people visit the High Line every year.

While the 606 Trail is arguably less of a tourist attraction, residents of Logan Square and Humboldt Park do not want a similar story to play out in their backyards. As Julia Thiel at Chicago Reader reported, neighborhood groups like the Logan Square Neighborhood Association are advocating for tax controls to help compensate for rising property taxes.

In the Logan Square/Avondale and Humboldt Park/Garfield Park areas, home prices are up 42 percent and 40.5 percent, respectively, from their lowest point during the recession. And the 606 will likely heighten that demand. According to Chicago Magazine, the hottest block in Humboldt Park is next to the 606. New single-family homes sold quickly for about $200,000 above the typical sale price on the block.

Another complicating factor is the area’s high concentration of small rental buildings. Our own analysis shows that 44.2 percent of parcels in the 606 area are two- to four-unit buildings. Those buildings were hit hardest by the recession, making up more than half of foreclosures in the 606 area. When these buildings go up for sale, they become prime picking for developers to buy up, renovate, or redevelop into single family homes and sell at higher prices.

Meanwhile, the eastern portion of the trail runs through Wicker Park and Bucktown, both more affluent areas with a greater percentage of owner-occupants. The trail may boost housing prices there too, but the risk of displacing residents is lower. Here, the trail is an added amenity in a neighborhood that is already too expensive for moderate- and low-income families, and not as attractive to developers looking for higher profit margins.

Ways to Avoid "Eco-Gentrification”

All this prompts major questions: Can the 606 dodge the mistakes of the High Line and boost quality of life without displacing residents? And, given the rental affordability crises in cities across the country, how can public works projects that “greenify” neighborhoods avert gentrification?

"The truth is that I can't wait for June 6," Delia Ramirez, a resident of the area for 25 years who is collaborating with the Logan Square Neighborhood Association, told the Chicago Reader before the trail opened. "It's a beautiful space. We just want to make sure we're going to be able to stay here to enjoy it."

Emily Badger, writing recently in the Washington Post, thinks we tend to oversimplify gentrification when tagging all new urban investments as causes of displacement.

“The more useful question isn't whether ‘gentrification’ is good or bad, but what it might look like to have new investment in a community that benefits existing and future residents alike,” Badger writes. “I know people who worry this isn't possible—that new investment and old residents cannot coexist, that the former can only displace the latter. But I'm convinced there must be a way to do this.”

One way to halt “eco-gentrification” might be simply to slow down, as The Guardian’s Jeanne Haffner suggests. Rather than large, dramatic waterfront projects, or flashy, world-class monuments, a piecemeal, “just green enough” strategy is more likely to introduce the type of green amenities that upper-income neighborhoods have long enjoyed without displacing poorer residents.

With all this taken into consideration, it's possible the trail could serve as a West Side landmark for everyone, rather than a path paving people out of the neighborhoods they have long called home.

Photo/Payton Chung