Rentals in Cook County remain unaffordable for the majority of low- and moderate-income households. Our latest report on the state of renting in Cook County finds a continued affordability crunch as more people became renters in the past ten years while the affordable supply declined.

This year’s report finds that the growth in renters is leveling off, but there are still about 182,000 more people who need low-cost housing than there are affordable apartments in Cook County. While at first glance the solution might seem to be to build more housing, it’s not that simple. As we show, every neighborhood has its own story.

The City Continues to Lose Affordable Units

While developers in the city have been building new apartments, most of them cater to higher-income renters, whose ranks are growing. In Cook County, the number of higher income renters (earning more than 120 percent of area median income) rose nearly three percent between 2015 and 2016, the largest increase among any income group.

Meanwhile, in neighborhoods across the city, Chicago is losing too many lower-priced apartments to rising rents, conversions of small apartments to single-family homes, and neglect. Since 2012, the county lost more than 15,000 two- and four-flats, a very common source of affordable rental housing. In some neighborhoods, these two- and four-flats are turning over as rents rise with growing demand or as neighborhoods gentrify and new owners turn a rental into a single family home. In other neighborhoods where disinvestment is more of a worry than gentrification, homes are being lost to neglect.

The result of these forces is a growing affordability gap in the city—the difference between the number of affordable units available versus the number of renters in need. Since 2012, the number of affordable rental units in Chicago has declined by more than 10 percent while demand for affordable rental units has declined by less than 5 percent over the same period.

The story in the suburbs improved slightly as demand for affordable rental housing decreased, but the affordability gap remains. “Affordable” for lower-income households is paying less than 30 percent of one’s monthly income for rent, a widely used barometer.

The top five city neighborhoods with the biggest affordability gaps are all lower-income neighborhoods, including Bronzeville/Hyde Park, Uptown/Rogers Park, Humboldt Park/Garfield Park, Austin/Belmont Cragin, and West Town/ Near West Side.

A Nationwide Crisis

Chicago is not alone, nor the most pressed, for affordable housing. An inauspicious “new normal” is that nearly half of renter households are burdened financially by paying nearly one-third of their income for housing, according to the Joint Center for Housing Studies. And most vulnerable, 43 percent of very low-income households are paying more than half their income in rent and living in severely rundown units. Very low income is earning less than 30 percent of the area median income, which in Cook County would be roughly $19,000 a year.

The reasons for the rising pressures differ. In some parts of the country, the high cost of building affordable housing is contributing to the crisis. And costs will only increase as the main tool used to finance affordable housing, the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, is losing some of its punch under the new corporate tax cuts. In other markets, overly tight zoning and NIMBYism are also to blame. In still others, stagnant wages and rising costs of living are choking out families. Some are asking whether this is a housing crisis or a wage and job crisis, Gina Ciganik of the Healthy Building Network told Curbed in 2016. "What are we subsidizing with affordable housing—low wages?”

The bottom line is that nationally there’s been essentially no growth in apartments renting for under $850 a month. Vacancies in these lower-cost apartments also remain low, according to the Joint Center for Housing Studies, while vacancy rates have been rising in the higher-priced segment as building continues. Vacancy rates in the lower-cost Class C segment was 4.1 percent in 2017 but 6 percent in Class A buildings in the third quarter of 2017.

The Solution Must be Tailored to the Neighborhood Market

The affordability gap needs to be closed, but how? As we have shown in other research, housing is unaffordable for different reasons, depending on the neighborhood.

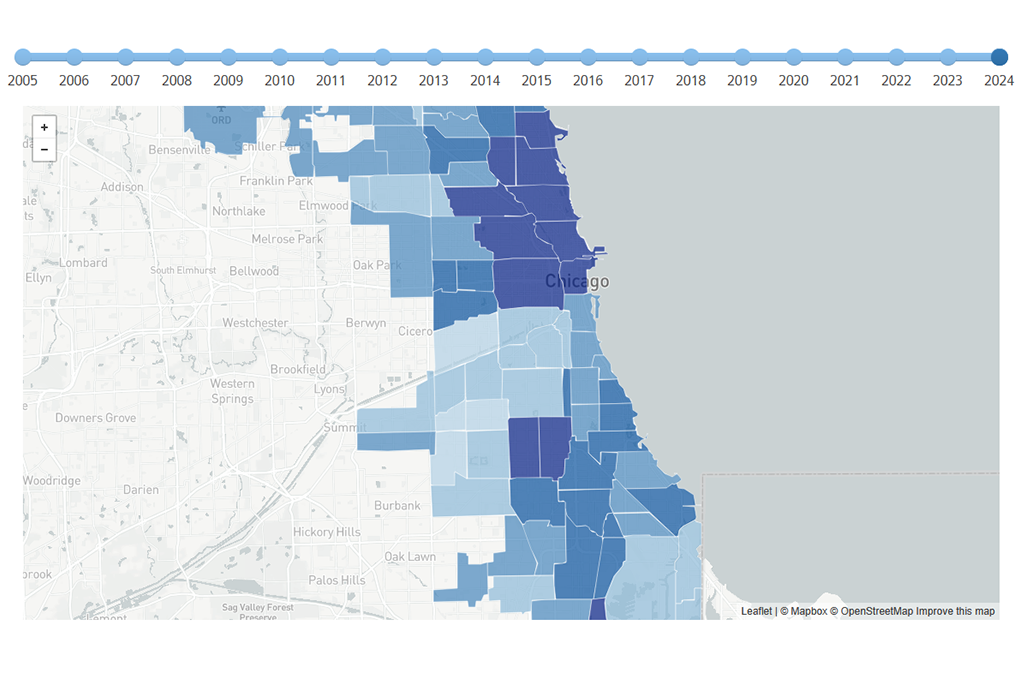

In distressed neighborhoods with concentrated poverty, low-cost apartments abound, but neighborhood residents still cannot afford them because their incomes are too low (dark blue on this map). South Shore, Englewood, and Garfield Park are all neighborhoods where building more housing would not ease the problem, but rather concentrate it. Instead, vouchers, operating subsidies, or more robust anti-poverty policies are needed to help families afford existing housing in these areas.

In contrast, more expensive neighborhoods such as Jefferson Park have little affordable housing but also little demand because lower-income families have been priced out of these neighborhoods. Creating more apartments with below-market rents, via subsidies or affordable housing inducements, would help lower- and moderate-income families enjoy the benefits of these neighborhoods. Combatting NIMBYism will likely come into play, as advocates and residents in Jefferson Park have learned.

Finally, in gentrifying neighborhoods such as Logan Square, homes are becoming unaffordable as once-affordable apartments are converted to single-family homes or rehabbed in order to command higher rent. Neighborhoods like these are losing affordable supply, putting affordability pressure on lower-income households. Here, a strategy to preserve affordable housing makes more sense. The Preservation Compact offers finance and policy strategies and resources for doing so.

Our new planning tool considers these unique market conditions and offers strategies for each.