The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a far-reaching public health crisis and economic recession. The number of unemployment claims has surpassed the number of new jobs created since the period after the Great Recession, and even as some states start to reopen and the impact of interventions mitigate some job losses, the number of laid-off workers continues to be extremely high.

How have policymakers responded to help communities weather the economic crisis resulting from COVID-19? This blog is part of our recent series examining the impact of the pandemic in Chicago neighborhoods and highlights local, state, and federal policy interventions that aim to provide housing and financial stability during a time of economic uncertainty. As the duration of large-scale unemployment and long-term impacts of the pandemic remain unclear, these policy approaches are evolving and fast-moving to respond to changing needs.

A Temporary Infusion of Cash Assistance

The economic fallout of the COVID-19 crisis is hitting lower-income households the hardest. In Chicago, our recent neighborhood-level analysis demonstrates that these more at-risk workers are very likely to be lower-income renters earning less than $30,000.

Getting cash assistance directly in the hands of individuals and families is a critical stopgap measure to stabilize households that are seeing their incomes plummet. The federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provided a one-time, income-adjusted payment and expanded the benefit amount, duration, and eligibility criteria of state unemployment insurance.

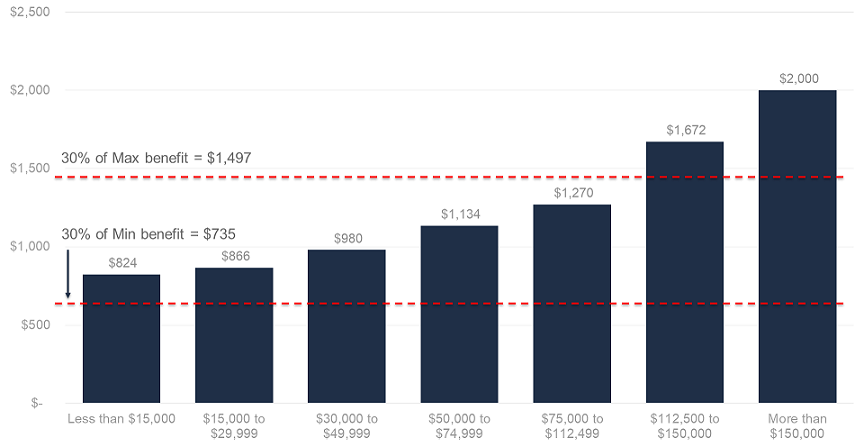

Initial research shows that the one-time payment was particularly vital for lower-income individuals to pay for essential goods and unpaid bills. For these households, half of the $1,200 payment was spent within ten days. Expanded unemployment benefits may have helped households keep up with their current housing costs and bills, but some renter households receiving these benefits may still experience rent shortfalls while expanded unemployment benefits are set to end in July (Figure 1).

When cash assistance is depleted and unemployment benefits expire, households may see their budgets strained, particularly lower-income households and already cost-burdened households with rents that eat up a large share of their income. The long-term impacts of the pandemic remain unclear and some workers may face prolonged periods of unemployment. Without supplemental housing assistance, households that have experienced income loss may use this cash assistance to prioritize other essential needs such as groceries and healthcare.

Cash assistance and unemployment benefits may offer temporary supports, but some individuals face greater challenges accessing these resources or are ineligible to receive them. Since the stimulus payment is disbursed through the IRS, individuals who do not usually file taxes must take extra steps to receive the payment. Individuals and families that lack access to adequate banking services may face hurdles seeing cash assistance materialize. Since the IRS opted to use Social Security numbers to disburse assistance, undocumented immigrants are ineligible for federal cash assistance and unemployment benefits, even though these workers are over-represented in some of the hardest-hit industries. Even for workers that qualify, states are grappling with such a large influx of unemployment claims that some workers face administrative hurdles accessing assistance.

Figure 1. Unemployment Benefits May Not Fully Cover Rents for Likely Impacted Renter Households

Median Rent of Chicago Renter Households with at Least One Member in a Vulnerable Occupation by Household Income Level, 2018

Source: 2018 ACS Microdata IPUMS USA, IHS calculations based on code developed by NYU Furman Center, Terner Center calculations

Stabilizing Households in Place

IHS analysis shows that in Chicago renter households are more likely to have one household member employed in an occupation experiencing COVID-19 related layoffs, and communities of color on the south and west sides of Chicago have high concentrations of vulnerable renter households. In six of these submarkets, over half of renter households have at least one worker more at-risk of COVID-19 related layoffs.

Some of these households were already experiencing housing insecurity prior to the crisis. Nearly half of Chicago’s potentially impacted renter households were already housing cost-burdened.

To respond to households at-risk of housing instability, a patchwork of local, state, and federal policies enacted temporary eviction and foreclosure moratoria. These protections aim to ensure residents have a stable environment to socially distance during a time when many households may not be able to make next month’s rent or mortgage payments. For households that have seen incomes plummet, these protections may protect against destabilization and potential homelessness.

The coverage and duration of these protections differ. Federal eviction and foreclosure moratoria apply to residents living in properties and homes with a federally backed mortgage - approximately one in four rental units and roughly 70 percent of home mortgages. Illinois has suspended all eviction filings for the duration of the Gubernatorial Disaster Proclamation. In some localities and states where these moratoria have not been established by legislative or executive action, housing court and physical evictions have been suspended. Massachusetts has suspended all phases of the eviction process, including the initiation of filing, housing court, and eviction enforcement. California is proposing a law that would prohibit servicers of federally backed mortgages from taking any foreclosure action for up to a year.

As states start to phase out shelter in place policies, housing courts are resuming eviction proceedings before additional state and federal housing relief measures have kicked in. Some homeowners are able to put a pause on their mortgage payments through forbearance, but renters have fewer options to delay rent payments. Policymakers are currently working to extend existing moratoria to avoid a wave of evictions and further destabilization. In the next federal aid package, the Health and Economic Recovery Omnibus Emergency Solutions (HEROES) Act, lawmakers are seeking to extend CARES Act moratoria to a year and cover all housing units, not only homes with a federally backed mortgage. In the meantime, organizations that provide legal counsel are working to connect tenants with representation and resources that keep vulnerable households stably housed.

Providing Emergency Housing Assistance Now

Temporarily pausing the clock may keep families protected in the short-term, but may lead to a future wave of eviction and foreclosure filings down the road. Nationwide, one in three renters and three in four lower-income adults do not have enough savings to weather a three-month economic emergency. Across Cook County, lower-income renters were more likely to be extremely housing cost-burdened prior to COVID-19 layoffs, paying more than half of their incomes toward housing costs (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Lower-Income Renters Experienced Higher Rates of Housing Cost Burdens Before the COVID-19 Economic Crisis

To provide longer-term relief, cities have gathered public and private funding sources, leveraged existing housing programs, and tapped into relationships with service providers to offer emergency housing assistance for households that have been hit hardest by income losses due to COVID-19 related layoffs. The City of Dallas’ Mortgage and Rental Assistance Program provided $13.7 million for rental and mortgage payment assistance for up to three months per household. Through the COVID-19 Housing Assistance Grant program, the City of Chicago partnered with local community organizations to distribute $1,000 grants to pay for housing costs.

These funds are critical for the households that receive them, but cities are limited in the number of households they can serve. While many industries affected by COVID-19 have ground to a halt, cities and states are experiencing fiscal stress and a drop off in tax revenues. Chicago’s housing assistance grants helped 2,000 households, but the program received 83,000 applications. A large-scale expansion of emergency housing assistance will likely require resources from the federal level. For example, the Illinois legislature amended the state’s FY 2021 budget to include $396 million in rental and mortgage assistance that draws from the federal Coronavirus Relief Fund.

Tenants are organizing rent strikes across the country and mortgage servicers have seen a rise in homeowners and property owners applying for mortgage forbearance. Some federal lawmakers are calling on the federal government to forgive housing payments throughout the duration of the crisis and create a relief fund to fully reimburse lost payments to landlords and mortgage holders. Additional federal policy proposals call for housing relief to be delivered through existing channels, such as through Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) Housing Choice Vouchers, Emergency Solution Grants, and Disaster Housing Assistance programs.

Established programs may be better positioned to disburse rental assistance to meet the scale of existing need, and since the administrative infrastructure is already in place, local housing authorities and practitioners may be able to deploy assistance at greater speeds. This approach is projected to cost far less since these programs are means-tested to target lower-income households. Expanding an existing program may also help garner public support and lay the groundwork to fully fund rental assistance programs in the future, which have historically received inadequate funding to meet existing needs.

Preserving Affordable Housing by Keeping Property Owners Afloat

Across the nation, landlords of small and mid-sized rental buildings provide a large portion of our communities’ affordable housing that is located in unsubsidized, smaller, and older rental buildings in lower-and moderate-cost neighborhoods.

Although these property owners provide a large share of Chicago’s affordable housing supply, they may have less access to resources to keep these units affordable, such as direct subsidies, and usually have narrower margins and small operating reserves. During the last recession’s recovery period, owners of mid-sized multifamily properties in Cook County’s lower- and moderate- cost markets received less mortgage credit compared to their counterparts in higher-cost markets.

A drop off in rent payments may prevent landlords of unsubsidized affordable housing from fully paying their mortgage, utilities, and maintenance costs and could lead to a domino effect that undermines the affordable housing supply. Deferred maintenance can lead to deterioration and poor housing conditions, putting existing residents at risk. When these landlords are unable to pay their mortgages and operating costs, existing affordable housing may be at increased risk of foreclosure and acquisition by investors who may not continue to provide affordable rents to the community.

Providers of subsidized affordable housing are also feeling the strain, although their access to federal subsidies may shield them from the immediate risks small landlords face. These developments, often owned and managed by nonprofits and public-private partnerships, are not profit-driven and depend on a mix of public funding sources. Across the country, these affordable housing providers are seeing anywhere between 10 to 40 percent reduction in rent payments.

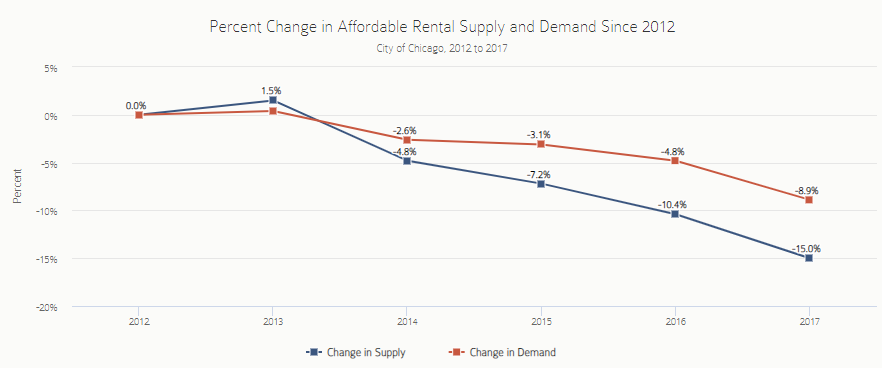

Chicago’s declining affordable rental stock (Figure 3) has contributed to the city’s large affordability gap, exacerbating housing cost burdens and limiting housing opportunities for lower-income renter households. Affordability pressures rooted in a shrinking affordable rental stock may also undermine neighborhood diversity, contribute to growing inequities, and heighten displacement risk. Within the last few years, 12 out of 13 Chicago submarkets with a shrinking share of affordable rentals also lost lower-income renters. In Chicago, four northwest side submarkets that saw substantial recent declines in affordable rentals also have large disparities between the share of white and Latinx workers more at-risk of unemployment from COVID-19. This raises concerns that a COVID-19-related economic downturn may amplify existing housing affordability pressures and accelerate displacement.

Figure 3. Chicago's Affordability Gap is Driven by Declining Supply of Affordable Rentals

Mortgage forbearance, debt modification, and repayment programs, and direct financial assistance can serve as lifelines to these property owners that are experiencing large-rent shortfalls. Chicago’s Emergency Relief for Affordable Multifamily Properties Program seeks to support 40 properties with grants and no-interest loans to subsidized affordable housing providers. New York has set up an emergency fund to provide small landlords with financial assistance.

However, providing landlords with partial financial assistance may still not cover their operating expenses and mortgage payments. Providing tenants with rental assistance can provide full relief to landlords and help the affordable housing ecosystem remain on stable ground. The Department of Housing and Urban Development is providing states and jurisdictions the flexibility to use Community Development Block Grants and funds from the HOME program to provide rental assistance directly to landlords.

Preventing Another Wave of Foreclosures

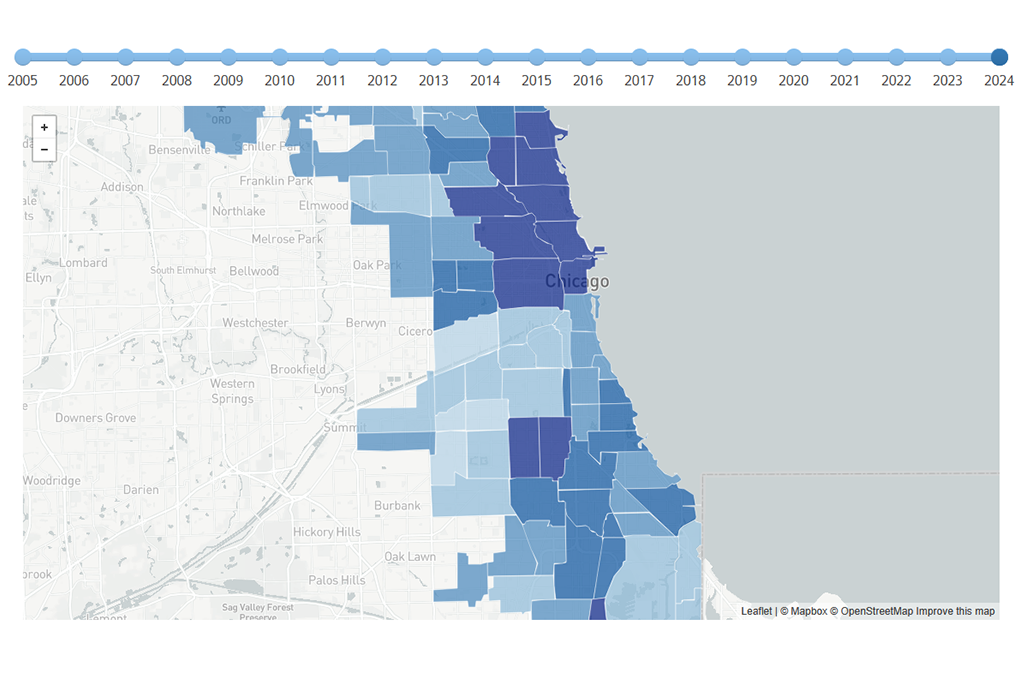

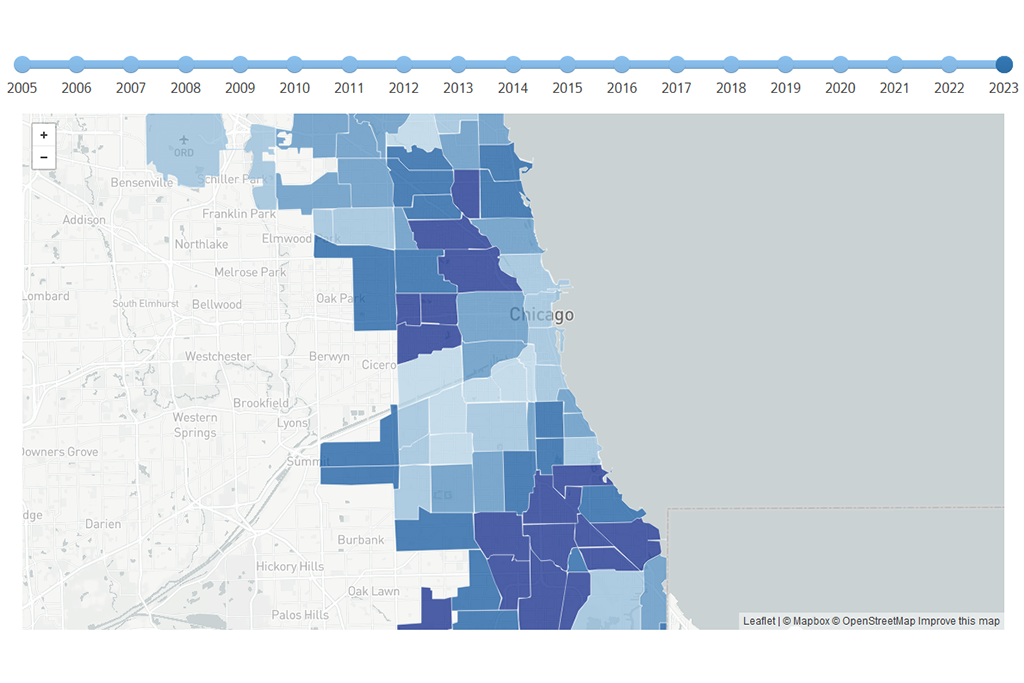

The legacy of foreclosure activity during the last recession still impacts homeowners and communities today. In many neighborhoods that experienced a high concentration of foreclosures during the Great Recession, home prices have just recently started to recover from the bottom of the market (Figure 4). Homeowners in these communities may remain underwater or near underwater and are at increased risk of foreclosure during this economic crisis. Avoiding more foreclosures is important to stem speculation, prevent homeowners from losing equity and wealth gains, and rebuild housing demand in communities hit hard by the last recession.

Figure 4. Concentrated Foreclosure in Chicago Neighborhoods Presents Recovery and Investment Challenges

A COVID-19 recession may not result in the tsunami wave of foreclosures seen during the last recession since mortgages today are less risky, but widespread unemployment means many homeowners are in financially vulnerable situations. Our analysis shows that across Cook County, the largest number of homeowners at-risk of initial job layoffs live in the south, southwest, and near northern suburbs. Although these owners are likely to be on more stable financial footing than renters more generally, vulnerable homeowners can be found throughout the County. The largest concentration of vulnerable homeowners that were already housing cost-burdened before the pandemic are located in several pockets in the city, near north, and south suburbs.

To prevent additional foreclosures during the COVID-19 crisis, Chicagoland housing counseling agencies are remotely providing their services to at-risk homeowners. These counselors have seen an uptick in calls since the crisis set in. In a survey conducted by Housing Action Illinois, over three-fourths of housing counseling agencies experienced increased calls for foreclosure prevention assistance. Despite increased demand, these housing counselors require additional funding to tap into better technology, increase capacity, and navigate existing and evolving homeowner relief programs.

Housing advocates have also looked to reinstate previous homeowner stabilization policies developed during the 2008 foreclosure crisis, such as loan modification programs that were available to all impacted homeowners and based on ability to pay. Federal agencies and Government Sponsored Enterprises have required banks and mortgage servicers of federally backed mortgages to provide homeowners with mortgage forbearance, deferral options, and repayment plans. In some cases, homeowners can meet missed payments when they refinance or sell their homes.

For mortgages that are not owned or insured by federal agencies, loan servicers may offer relief options on a case by case basis but are not required to under the existing CARES Act. Chicago leaders and participating banks have signed a nonbinding agreement to provide temporary mortgage forbearance to homeowners facing financial hardship. However, the availability of existing homeowner relief options depends on which entity owns the mortgage rather than financial hardship.

Moving Forward, Not Backward

Similar to the Great Recession, this economic crisis risks the possibility of deepening socioeconomic and racial inequities. To adequately address the economic crisis brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, affordable housing policymakers, and community development practitioners face a challenging prospect: balancing immediate relief with equitable, long term recovery.

Through our applied research model, IHS will continue to produce data and information that supports Chicago-area housing and community development practitioners and stakeholders in this important work. In the coming months, IHS will develop new analyses to help regional stakeholders understand the potential scale and patterns of a COVID-19-related economic downturn on local housing markets and continue to work with community partners to develop new data indicators and tools to support their work on the ground. IHS is also actively collaborating with partners to leverage applied research and stakeholder engagement to inform innovative policy development that mitigates the local impacts of COVID-19 on our communities and advances a more equitable recovery.

For more information on technical assistance inquiries, contact IHS. To keep up-to-date on IHS analysis, sign up for our email list, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn.