Photo: Evelyn Ryan

Property taxes are one of the most significant annual costs for homeowners. Property tax increases can disproportionately impact modest-income households, and there are concerns that this is intensified in neighborhoods with rapidly rising house prices. This blog contextualizes recent research and reporting on property tax disparities in Chicago with IHS research on neighborhood house price changes and discusses how policy interventions designed to mitigate increased tax burdens have challenges of their own.

In December, the Cook County Treasurer mailed 2021 tax bills to local property owners. In the City of Chicago, taxes on properties rose 6.6 percent compared to the previous year. However, the impact of these increases did not fall evenly across all property owners. Residential property owners in Chicago bore the brunt of tax increases with an 8 percent hike, while taxes for commercial properties only rose about 5 percent. Additionally, according to a recent report published by the Cook County Treasurer’s Office, many of the City of Chicago’s largest tax increases were seen by homeowners in gentrifying Latino communities on the city’s North and Northwest sides.

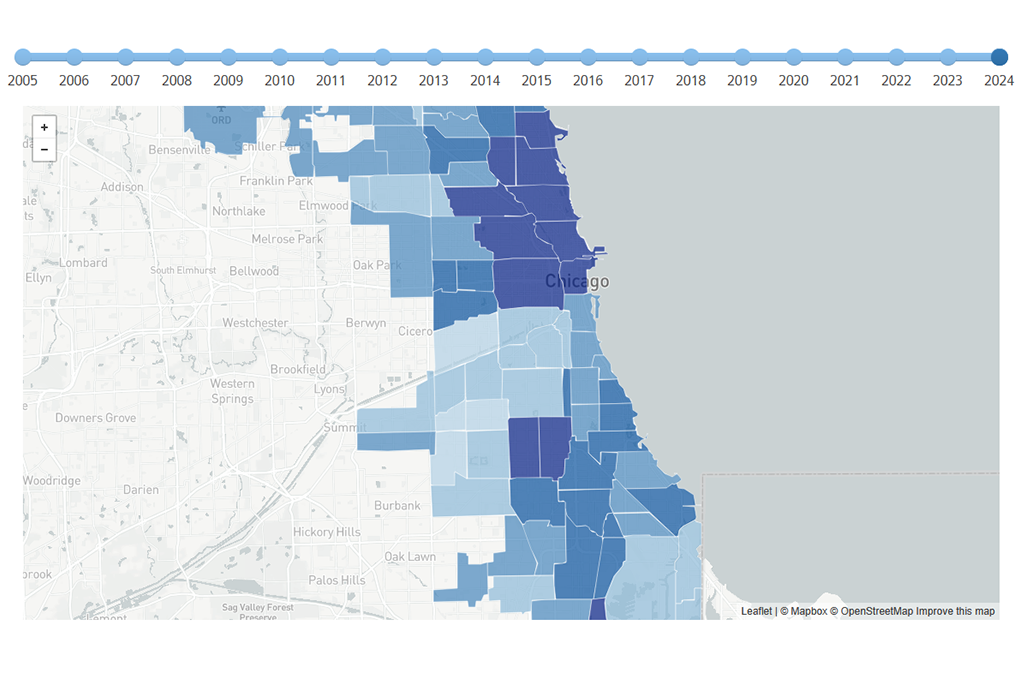

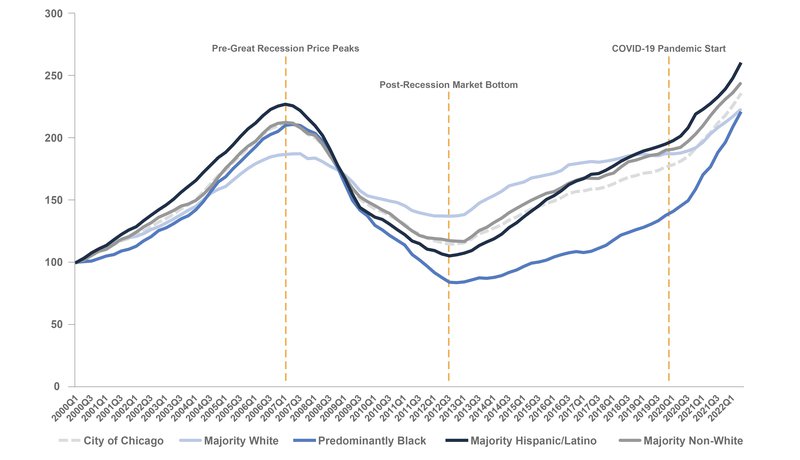

These increases reflect the implications of broader market trends in home prices observed in recent IHS research. In November, we updated our Cook County House Price Index to include the second quarter of 2022. The index tracks quarterly changes in single-family house prices across Cook County including in 16 Chicago submarkets. When examining neighborhoods by race/ethnic composition in a separate and expanded analysis, the data indicate that majority Hispanic/Latino neighborhoods have seen some of the largest overall price gains over the past decade. Majority Hispanic/Latino neighborhoods saw prices increase by over 146 percent since 2012 while on average, prices across Chicago increased by roughly 105 percent.

Figure 1. IHS House Price Index by City of Chicago Neighborhood Racial or Ethnic Typology, 2000 to 2Q 2022

Source: IHS Cook County House Price Index

Rising property values, property taxes, and disproportionate impacts

Rising property values have numerous implications for a neighborhood and individual homeowners. They are a positive indicator of housing demand in the area, investment in the neighborhood, and the ability of existing owners to build wealth through home equity. However, there are also potential downsides if prices rise too rapidly compared to other neighborhoods within a taxing district, including increased property tax burdens.

While property taxes don't necessarily increase at the same rate as home values, the estimated market value of a home is a key factor in the calculation of a tax bill. If the value of a homeowner’s property increases faster than the average of all other properties in the taxing district, the share of the total tax bill owed by that homeowner will increase. Increased property taxes can be particularly burdensome for long-term owners and modest- or fixed-income households and can also contribute to affordability and displacement pressures as homeowners contend with increased housing costs and landlords pass the tax burden onto tenants through higher rents. Recent reporting in rapidly changing Chicago neighborhoods such as Pilsen, where the supply of lower-cost rental units has significantly dried up in the past decade, highlighted the stories of homeowners struggling with recent tax bill increases, which in some cases have been by thousands of dollars.

Property taxes are often a much larger burden on lower-income families than wealthier households. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy found that in 2018, the poorest 20 percent of taxpayers paid 4.2 percent of their income on property taxes, compared to 3 percent of income for middle-income taxpayers and 1.7 percent of income for the wealthiest 1 percent of households. Other research has found that these tax disparities are felt strongest by Black and Hispanic residents who are estimated to have a 10 to 13 percent higher property tax burden than households more generally. A study from the Center for Municipal Finance found that this disproportionate burden is, at least in part, a result of regressive tax assessments in which more affordable properties are often assessed above their true market value and expensive properties are assessed below their true market value.

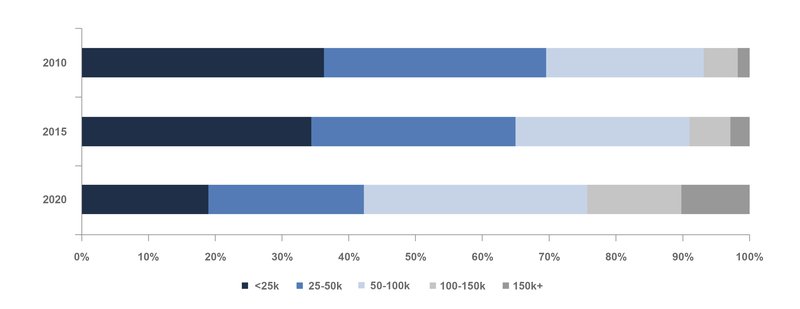

This regressive effect is intensified in gentrifying areas. These neighborhoods typically include many modest-income, long-term owners who may have purchased their homes decades before the more recent influx of higher-income residents moving to the community. In a neighborhood like Pilsen, this type of neighborhood change can be seen in the shifting composition of household incomes. For example, between 2010 and 2020, the percentage of Pilsen households making less than $50,000 decreased by about 30 percentage points, while those making over $100,000 more than tripled. These wealthier newcomers are likely better equipped to absorb rising tax burdens and rents, while longtime lower-income residents, especially those on fixed incomes, are more likely to be overwhelmed and potentially displaced.

Figure 2. Composition of Lower West Side (Pilsen) Households by Income, 2010-2020

Source: Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University Analysis of American Community Survey 5-Year Estimate, 2006-2010, 2011-2015, and 2016-2020

Challenges around mitigating the disproportionate impact of property tax increases on modest-income households and households of color

Large increases in monthly costs present challenges to the sustainability of homeownership for many low- and moderate- or fixed-income households, and property tax burdens have been found to represent a particularly volatile component of an expected house payment.

There are various policies in place to help those struggling with rising tax burdens. Illinois has a General Homestead Exemption that allows homeowners in Cook County to reduce their bills by up to $10,000 if eligible, as well as various other exemptions, such as the “Senior Freeze” and long-time owner exemptions. The state has the Senior Citizen Real Estate Tax Deferral Program, which allows seniors making $55,000 a year or less to defer up to $5,000 a year in taxes on their primary home, but they are required to pay six percent interest per year payable upon death or home ownership transfer. Illinois also has rate and levy limits, which restrict the amount a municipality can increase taxes per year. These rate limits don’t necessarily apply in home rule jurisdictions such as Chicago, but the city passed an ordinance limiting annual tax levy increases. Expanded reforms to mitigate property tax burdens are often unpopular – either with the broader tax base to whom the tax burden shifts when interventions are applied to some property owners or tax classes or with state legislatures that have to otherwise pay the bill. In Illinois, state funding for a circuit breaker program that limited the amount of tax for modest-income older adult homeowners and homeowners with disabilities was not renewed after 2012 to help balance the state's budget.

Ultimately, many exemption programs are flat amounts. Therefore they may decrease in benefit as assessed values increase and may be insufficient to protect cost-burdened households from the financial burden of large property tax increases. Additionally, more robust exemptions like the long-term homeowner exemption are applied to a narrow set of homeowners and have a limited reach. Further, research has found that disparities exist in the use of exemptions by homeowners. Similar racial, ethnic, and income disparities have been observed in the outcome of property tax appeals, a mechanism for contesting property taxes, heightening their regressivity. In conjunction with disparities in exemption use and in assessed values, these factors lead to a persistent "assessment gap" that places a heavier burden on households of color.

In gentrifying neighborhoods with rising values due to new demand for housing from higher-income households, rising tax bills likely amplify the already existing housing cost strains experienced by low- and moderate-income, fixed-income homeowners and homeowners of color. Further, policy interventions to mitigate the impact of property tax increases are most often utilized by wealthier homeowners with higher property values and in neighborhoods with fewer residents of color – heightening regressivity and undermining a key opportunity to better balance property tax burdens.

Homeownership is a key wealth-building tool for households and communities of color. Leveraging homeownership strategies that create new and sustain existing homeowners will likely require the continued development and expansion of policies that mitigate the impacts of rapid price gains and shifting tax property tax burdens on modest-income households and households of color.