Projects like the 606 Trail in Chicago need safeguards that ensure diverse communities.

New amenities in an older neighborhood can be a blessing and a curse. Just ask the West Chelsea residents who live near the New York City’s High Line Park, or residents of the Logan Square neighborhood in Chicago who live near the new Bloomingdale Trail. “It breaks my heart,” said Logan Square resident Lucy Gomez-Feliciano of the new trail’s impact on the neighborhood.

Gomez-Feliciano, who has lived in Logan Square for 19 years and is the Health Outreach Director/Active Living for the Logan Square Neighborhood Association, was an early advocate of the Bloomingdale Trail, a repurposed rail track that has created a much-needed green space for neighbors. But now, as home prices escalate, some of the working-class families in the vicinity are starting to wonder what the future holds. “People who can retire and sell, good for them,” Gomez-Feliciano told me. “But what about those of us raising our kids here, who want to stay in the neighborhood?”

The question that goes unanswered in these projects, she says, is how do you do both? How do you improve the neighborhood while maintaining economic diversity?

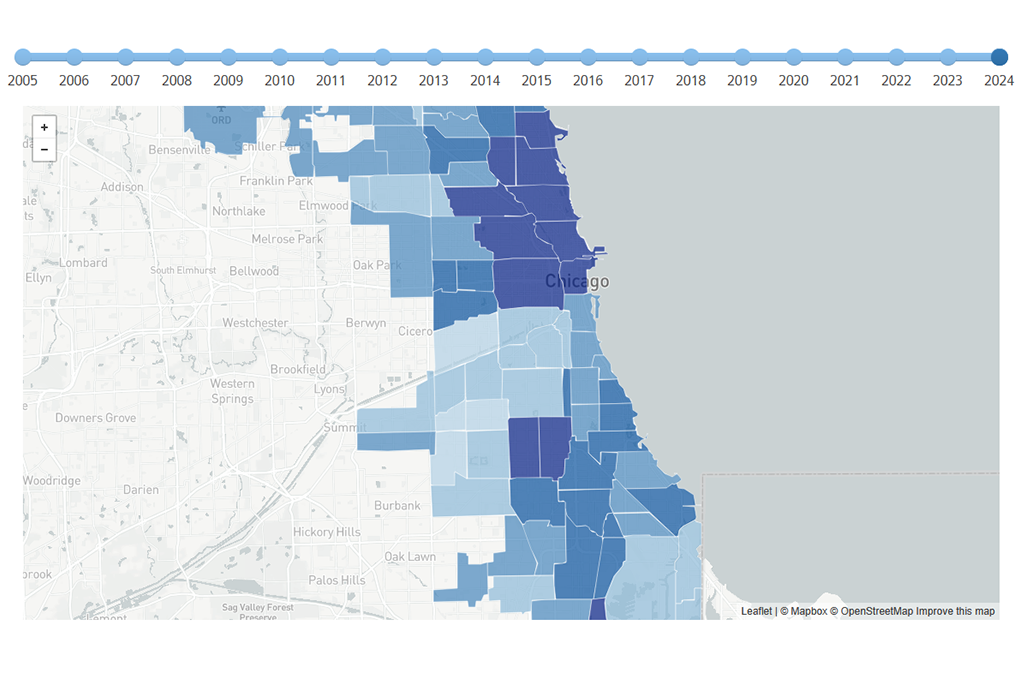

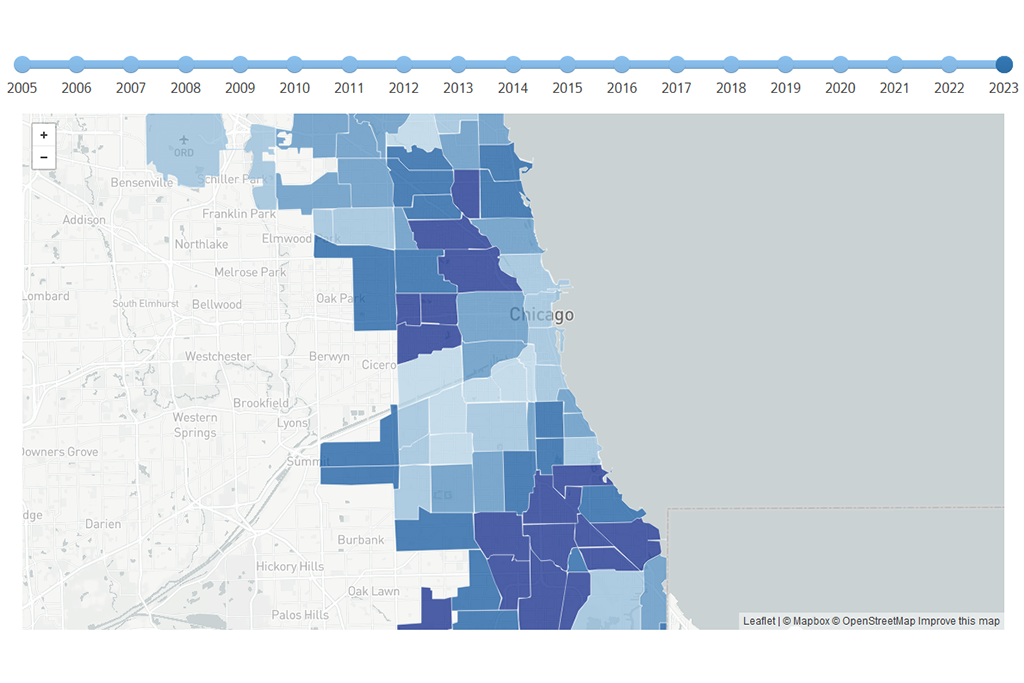

That’s a question we’re trying to answer in a new project funded by the Polk Bros. Foundation. IHS will conduct policy impact analyses using our price index, housing market indicators, and data clearinghouse, and work with Logan Square neighborhood groups to understand market conditions. With data and information in hand, residents can more effectively pursue tax appeals and other strategies to ensure continued affordability. The grant will also help us complete a broader analysis of how other places are grappling with place-based investments and accelerated neighborhood change.

Many of these thorny issues were raised at a December 3 conference on the impact of trails and green spaces on real estate and economic development hosted by DePaul University’s Real Estate Center. The conference featured lessons from three recent “greening” projects in New Orleans, Chicago, and Atlanta.

In the “largest social experiment in the city’s history,” says Paul Morris, Atlanta built a 22-mile trail and parkway—the Beltline—in the heart of the city in an effort to bring life back to the core and “get people to unite in a city that has historically been divided.” The project is working, says Morris, the president and CEO of Atlanta BeltLine Inc.

Chicago’s Bloomingdale Trail (also known as the 606 Trail) had different but equally ambitious aims. The 606 | Trust for Public Land was, among other things, seeking to ensure that residents had ready access to much-needed green space, Jamie Simone, program director at Chicago Urban Parks at the Trust for Public Land, told conference attendees. The trust’s national arm seeks to ensure that every person in the United States lives within a 10-minute walk to a park or open space. Logan Square, in particular, lacked parks. As Simone described it, the community was on board from the start. And why not? The trail would give kids a place to play, and families a place to walk, exercise, and socialize. It would bring shoppers to neighborhood stores and restaurants, and inject money into the local economy.

But what happens after the ribbon cutting is often left to the marketplace. Urban designers create exciting ideas for parks, cities and public-private partnerships raise the capital, the park gets built, and the ribbon is cut. Then long-time residents are left to deal with the future of rising property taxes and declining affordability.

Of course, cities are all about change and turnover. "It's not like you can keep things frozen in time,” writes Jennifer Wolch, dean of the College of Environmental Design at UC Berkeley and an advocate for “just green enough” approaches. “You don't ever want to make the argument that in a poor neighborhood you don't want to build something wonderful because it's going to trigger gentrification."

But upward mobility should not mean displacement. “What we need,” wrote Mindy Thompson Fullilove, a psychiatrist who focuses on the impact of urban planning on residents, “are equitable programs that give all of us a chance to live in a kind and beautiful place.”

That takes planning, smart policies, and community input. Options might include homestead legislation, tax abatement for seniors or long-term residents, or affordable-housing requirements in new construction. Renters are often the hardest hit, and policies addressed specifically to renters are vital as well.

Reyna Luna, an activist for Grassroots Illinois Action, summed it up in a word: education. “Homeowners need to learn about the values of their homes and how to fight displacement, and newcomers need to learn about the culture of the people who already live there.”

The IHS project will help residents make smart choices, and inform policy going forward on how best to introduce amenities without displacing those who have raised their children in the neighborhood and want to stay.