A conversation with Robert Chaskin and Mark Joseph

In their recent book, “Integrating the Inner City: The Promise and Perils of Mixed-Income Public Housing Transformation,” Robert Chaskin and Mark Joseph detail the demolition of Chicago’s high-rise public housing and the growth of mixed-income developments under Chicago’s Plan for Transformation. The plan is the country’s largest attempt at mixed-income public housing reform.

Under the plan, more than 40,000 public housing units have been demolished or renovated, and ultimately 7,000 replacement public housing units are projected to be integrated among apartments, condos, and townhomes in newly built mixed-income communities. The cost of the redevelopment (to date) has been more than $3.2 billion. Today, these emerging mixed-income developments include buyers and renters whose homes sell or rent for the market rate; buyers and renters who receive a subsidy to cover about 70 percent of housing costs; and relocated public housing residents who live in units owned by the Chicago Housing Authority and who pay a small portion of their income toward rent.

Drawing on six years of in-depth fieldwork, the book chronicles the successes, struggles, and missed opportunities at three sites: Oakwood Shores in North Kenwood-Oakland, which replaced the Ida B. Wells homes; Park Boulevard in Bronzeville, which replaced Stateway Gardens; and Westhaven Park in the city’s Near West Side, which replaced the Henry Horner Homes.

Although the sites are well populated, though not fully built out, the integrationist aims of mixing lower- and higher-income families are less successful as the social distance between relocated public housing residents and others remains a dividing line. Use of public space, for example, was contentious. “When I come home from a hard day’s work,” said one homeowner, “I really don’t want to see people hanging out on the front porch.” Others weren’t used to so many children in the hallways and sidewalks. On the other hand, the public housing residents felt snubbed—“people walk right past you”—and constantly under surveillance. The few times the two groups of public housing renters and the other renters and owners came together were at crime-watch meetings, where low-income residents felt stigmatized and singled-out.

Those are just a few of the misgivings and misperceptions that Chaskin and Joseph chronicle, while also providing sharp insights into how to do “mixed income” better. In conjunction with the release of our report on the state of the rental market in Cook County, we spoke with them, both longtime community development scholars, about their book, and what their findings mean for affordable and diverse housing in the city.

IHS: Mixed-income public housing transformation seems logical after the failure of Chicago’s high-rise public housing, where we essentially isolated poor families in housing that was physically and socially cut off from the rest of the city and where we let the buildings deteriorate on a grand scale. But your book points to an uphill climb for mixed-income developments, in Chicago at least. Why is it so hard?

MARK JOSEPH: The logic is that concentrated poverty is a massive problem and we have to do something different. We can’t keep warehousing the poor in dense, isolated developments. But that logic breaks down when you say the opposite, that integrating housing developments must be an improvement.

It takes more than just building new homes. What we learned is that by the time the development partners get to the phase of community building, they’re just burned out. There are so many phases, including financing, and relocation of public housing residents, and demolition of the old units, and then screening potential residents and marketing the development, and then getting everyone back in. And we put a lot of focus on those other phases, but there’s no one whose primary job it is to think about making the community work at the end of the day. And that’s the time when to roll up your sleeves. So that falls through the cracks.

ROBERT CHASKIN: Breaking down segregation is the right thing to do, but it’s hard to do. There’s an enduring legacy of race and racism, and public housing residents are tarred with a sense of the “urban poor.” For both people trying to do these redevelopments and service providers, and many of their higher-income neighbors, the notion of public housing residents as an urban “underclass” shapes their sense of “the other” in these neighborhoods. The legacy of public housing conditions how people respond to them in these environments.

Also, in the mixed-income developments, the two groups of residents have a fundamentally different orientation about what urban living should look like. Take private versus civic space, for example. There were disagreements about what behavior is appropriate in public. Homeowners wanted people to stay in the back yard for barbecues and socializing, but public housing residents say, “You don’t see anyone to say hello to if you’re out back.” The two groups don’t share the same idea about neighborhood sociability. The social distance between the most and least disadvantaged is exacerbated in some ways by their own new proximity. And the fact that these are new neighborhoods made in some ways out of whole cloth, but on the footprint of communities that public housing residents lived in prior to demolition further complicates things.

IHS: Are we privileging the market—homeowners and sellers—over community-building? In the book, it seems that the owners have more say in how things are done in the developments. They have their board meetings where renters are not allowed a vote, for example, and renters therefore rarely attend. There are market pressures in the developments, to turn a profit for the developers, to ensure homeowners can sell at a profit if they choose to leave, and to attract higher-income families to live there in the first place. No one wants to lose money on a home they buy, after all.

RC: Because it has to work as a private housing development (it must attract homeowners), there’s something very fraught about that dynamic. Homeowners fundamentally shape how the developments are managed, and their concerns about property value and security led to a rather draconian regime of monitoring and surveillance and sanction. Perhaps if you had more variation in price points and kinds of places to attract a broader diversity of residents, you’d maybe break down that binary [market rate vs. public housing]. Scattered site housing in better-off neighborhoods is often less problematic in this regard. Residents have access to amenities of the neighborhood and they are not targeted in the same way because the whole issue is not as fraught.

IHS: What would make it work?

RC: Engagement on equal footing is key. You also have to couple investment in affordable housing with broader investment in community development and economic development and in better connecting poor neighborhoods to the city.

MJ: Fit and matching. We need to get smarter and more sophisticated about matching households with various housing options. Mixed income is not right for everyone, but it is for some. For others, a voucher or a well-managed public housing development might be a better fit. Even every mixed-income development is different. Would Oakwood Shores work for you or would another one be better? All these things matter.

IHS: Can you engineer “neighborhood”?

MJ: Yes. To think it’s going to happen organically is folly. I get a lot of pushback about that because in richer communities no one is necessarily social engineering engagement. But here, you’re reordering a turf and bringing in a whole set of players, and now they have to share that new turf together. And it takes real support and nurturing to do that. But not only on the part of public housing residents. We need a lot better education of the market-rate buyers. They need to know the history of the community, the pride and traditions. They need to understand what it took for these families to get here, what they went through for eight years. It’s delicate, intricate work.

IHS: You write that the city has so far lost about 14,000 public housing units since the Plan for Transformation. What is the impact of the loss of that much affordable housing on families and on the city?

MJ: It’s devastating. It questions who gets to live in the city. And it challenges the identity of the city. It also makes life that much more tenuous for struggling residents because either folks are homeless in one form or another—moving around, couch surfing—or they’re forced to accept an even lower quality of housing because that’s what they have access to.

One positive thing about public housing—you know who your landlord is and you’re in a system that gives you some rights. With folks in the private market, it’s a crapshoot how ethical and competent your landlord will be. You may have to put up with subpar housing or increased mobility.

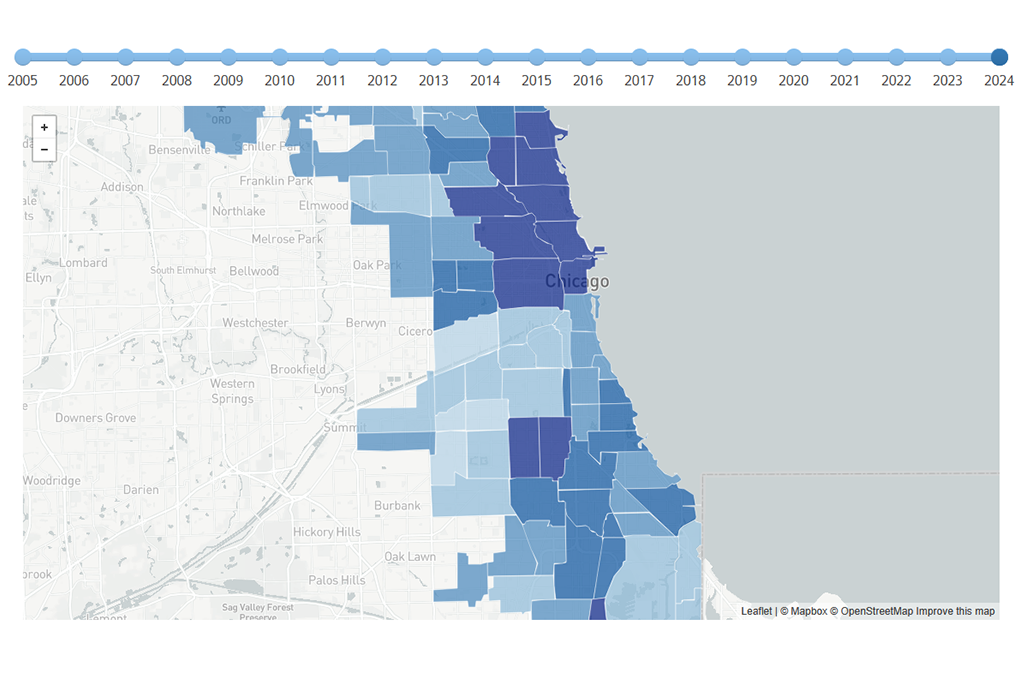

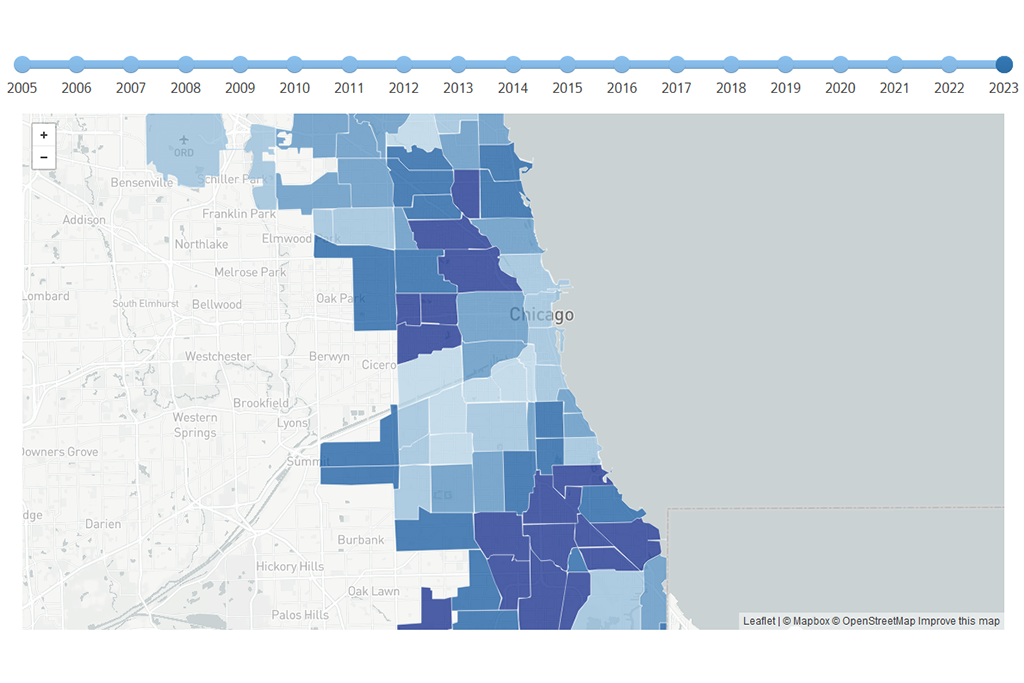

RC: Chicago has done a fairly successful job in becoming a global city. We’re attracting more affluent people to live in the city, and the scale of development is returning after the downturn. But it’s still a tight rental market and there are fewer and fewer places for people who don’t make good livings to live. In many ways, we’re reproducing segregation, but by income too. Poor people are going to peripheral neighborhoods that have fewer supports for them, or they’re going to inner-ring suburbs with even fewer supports. So you are creating the city as an exclusive place for the affluent. That’s a loss.

IHS: Should we give up on mixed-income housing?

RC: I think it can work, and it may work very well, but it’s not the only tool in the shed and it may not be the best one. Fundamentally we just don’t have enough affordable housing. That’s foundational. So we want to build affordable housing that doesn’t exacerbate segregation and concentrated poverty. And that means building not only in struggling neighborhoods. And it may mean more scattered-site public housing and housing at a small scale and integrated into the neighborhoods. And we need to couple affordable housing with more investment in community development, so in working-class and poor neighborhoods we’re also contributing to the capacity of neighborhoods to do well and be better connected to a city more broadly. More inclusionary zoning in well-functioning neighborhoods is also needed, with fewer “outs” for developers. And it must be truly affordable, not 80-120 percent of area median income, but lower.

MJ: No one approach is a silver bullet, but from a

policy level, we need a suite of options to replace concentrated poverty

and each option needs to have social supports and resources that go along with

it. Voucher holders don’t have social supports now. Our

research has shown that among four affordable housing options, the most

precarious families were the households with vouchers. Families doing the best

were in scattered site housing. The middle ground were those who moved into

mixed-income developments or back to 100 percent public housing.

IHS: I can’t help but wonder, as we did with high-rise public housing,

will we look back in 20 years on mixed-income developments here in Chicago and

shake our heads and say, what were we thinking?

RC: We’re already shaking out heads. I think the jury is still out on how this will play out over the long term.

MC: I think we may be incredulous that we didn’t go the extra mile to make these places work. Hopefully in 20 years, this time will be an inflection point where you began to see people be so much smarter about how they did this. We figured out how to build them, but building is not enough. Maybe in 20 years, mixed income will have gone to scale, with mixed income neighborhoods, not just developments, and mixed income will no longer be delineated by race and income so clearly. I still think there’s room among well-meaning policy and practitioners to do this more effectively.

Robert Chaskin is professor and deputy dean for strategic initiatives at the University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration. He has written widely on the topics of neighborhood intervention, community capacity building, and the dynamics of participatory planning and neighborhood governance.

Mark Joseph is associate professor at the Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences at Case Western Reserve University, director of the National Initiative on Mixed-Income Communities and faculty associate at the Center on Urban Poverty and Community Development. His general research interests are urban poverty and community development.

Photo/Barbara Ray