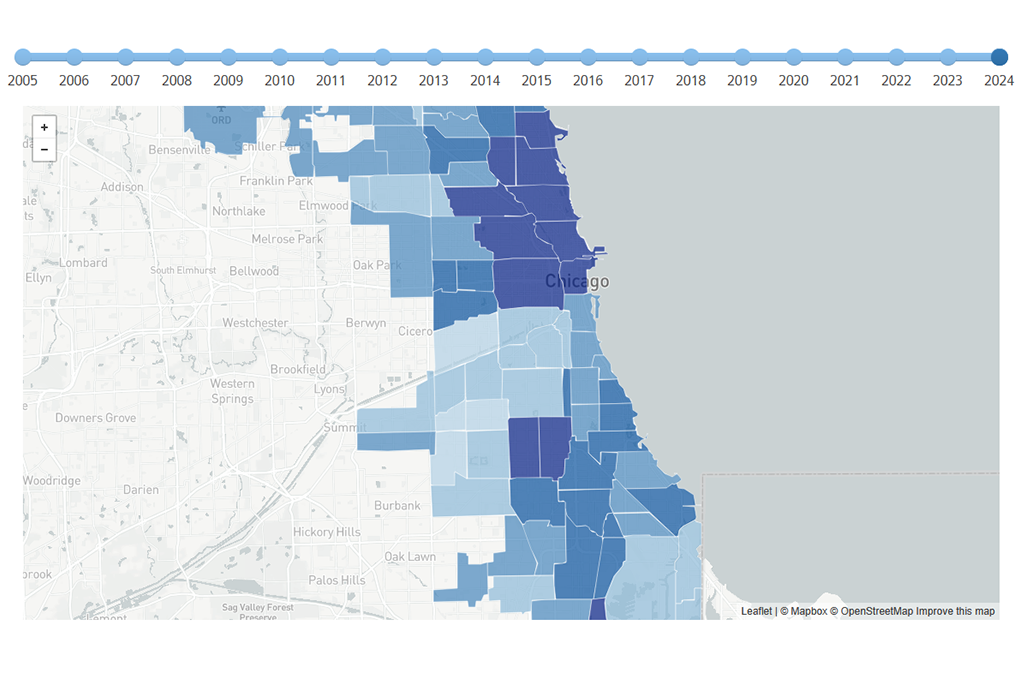

In December, we released an analysis and interactive map to help Chicago communities better understand gentrification pressures and the risk of displacement in their neighborhood. The tool identifies areas where home prices have appreciated faster than citywide averages and where a significant share of residents is vulnerable to displacement.

We recently discussed the map with three people who are on the frontlines of the housing affordability debate in the city. Diane Limas is board president for Communities United in Albany Park, an area acutely feeling the pressures of gentrification. Roberto Requejo is heading up Elevated Chicago, a regional coalition working to remedy inequitable development and close disparities across neighborhoods. And Stacie Young is director of the Preservation Compact, which focuses on preserving affordable housing in both strong and weaker markets.

Acting Before It’s Too Late

Albany Park is under pressure. A traditional gateway for immigrant families in Chicago, cash investors have been buying up the iconic two- and four-flat apartment buildings and making them into single-family homes for higher-income buyers, according to longtime activist Diane Limas of Communities United. As a result, long-time residents are migrating west in search of cheaper housing.

Limas says, “It is Latino working families who are being displaced—our black and brown communities.”

To compete with the cash buyers, Communities United partnered with the Chicago Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., a nonprofit developer, who had the cash to buy properties in the neighborhood quickly and keep rents low. To date, they’ve preserved 42 units of affordable housing in Albany Park and elsewhere. But the pressure is immense.

“The city’s Department of Planning doesn’t think it’s as important to preserve affordable housing as it is to build new affordable housing,” Limas says, because in their mind, new development means no displacement.

“But as developers are buying properties and evicting families, it’s hurting our communities and taking away our diversity,” she says.

The mapping tool, she states, is invaluable to their fight.

The tool allows nonprofit developers to see the emerging hot spots and buy up property while it is still affordable. “Think how many more properties we could have purchased if we’d purchased them four years ago.”

The maps, she says, also allow people to organize for the coming changes. “You can organize residents and say ok city, prices are going high, people are going to be displaced, what are you doing to preserve affordable housing there?”

Limas says that data makes their arguments that much more compelling.

Banding Together for Bigger Impact Citywide

To Roberto Requejo, the fact that 100,000 or more African Americans have left Chicago in the past 10 years is a warning sign. “When we talk about displacement, we seldom talk about this,” he said. The exodus, he believes, represents a different source of displacement. “Not necessarily from gentrification,” he says, but “displacement by disinvestment.”

Instead of “politics at its worst,” he continues, with local gubernatorial candidates trading barbs about the displacement, residents, activists, and politicians could use the mapping tool to raise awareness of this issue and target resources accordingly.

“Using the maps, you can go back 10 or 20 years and see the actual trend of disinvestment. We as a city have not been paying proper attention to this.”

The mapping tool, Requejo believes, can bring city neighborhoods together in new ways. Instead of a fragmented neighborhood-by-neighborhood response to gentrification and disinvestment, communities can put a coordinated, citywide plan in place.

The analysis that accompanies the mapping tool, he says, is helpful because it shows what policies communities should adopt depending on the type of market presence in each locale.

Weak Markets Are Another Story

Stacie Young sees it a bit differently. Chicago, she says, is not a San Francisco or Portland, with their intense and widespread gentrification pressures. Sure, some neighborhoods are feeling it, but frankly, she says, some Chicago neighborhoods would welcome a little investment. Like Requejo, Young thinks the focus in many neighborhoods should be on disinvestment.

“The threat is not actually displacement,” says Young, “but continued lack of investment.”

Young believes the map comes in handy for targeting scarce investment dollars. “You don’t want to be using a bucket of money to preserve two- and four-flats in a neighborhood that really doesn’t have much pressure anyway,” she says. This map can identify where the hot spots are.

In the end, data like this must always be coupled with boots-on-the-ground knowledge. It is a tool to add to the arsenal of voices and activism, says Limas.

“Imagine if we could take this data plus testimony from principals and pastors and make our case to preserve affordable housing. That’d be compelling,” she says. “Data is the way we’re going to convince them to make changes.”