HUD’s prospects under Ben Carson and ways to build more affordable housing despite it all

Finding an affordable apartment is nearly impossible for those living on the margins, thanks in part to the shortfall of about 7.4 million affordable units nationally. And if the pundits are right, things may get worse before they get better.

The $54 billion proposed cut in nonmilitary discretionary domestic programs by the Trump administration has to start somewhere, and HUD is a target, according to advocates.

As Housing Wire summed it up: “Priorities during this administration could create problems for the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s assistance programs as more focus is placed on military spending and less on housing.”

Ben Carson, recently sworn in as HUD’s new secretary, is being elusive , according to The Atlantic. He “consistently pledged to keep [programs] going,” the Atlantic reports, including “rental-assistance demonstration… a community-development block grant that will provide $1.6 billion to Americans, … and a program to rid housing of lead hazards. In fact, he said, a program to end veteran homelessness ‘needs more enhancements.’”

Yet his aversion to the bureaucracy at HUD is clear. So too is his aversion to “failed socialist experiments in this country,” of which public housing is one.

When asked by Sen. Thom Tillis [R-NC] in his confirmation hearing whether he thought the country has swung from “providing housing to providing warehousing for an unacceptable number of people who are supported through the federal government?” Carson answered, “yes, absolutely.”

Panelists at a recent housing conference interpreted that as code for requiring more job requirements and time limits in public housing”—even though, as the Urban Institute notes, one-third of public housing residents are seniors and one in five has a disability. Nevertheless, the Urban Institute writes, “calls to promote self-sufficiency or impose work requirements often assume that all public housing residents are able and should be willing to work.”

The “warehousing” philosophy was evident in the House Financial Services Committee 2018 government budget meeting in February. During that meeting, the committee voted to express a position against expanding the Housing Choice Voucher program because, they said, not enough is being done to address the “root cause” of families’ housing woes.

“For all its good intentions,” the committee wrote, "the federal government’s public policy response to the very real housing needs of low- and middle-income Americans has fallen far short of success…because [housing programs] are not designed to address the root cause of housing need: the underlying problem of generational poverty. …" Accordingly, they continued, it is time to reform housing assistance “with a higher purpose than simply perpetuating programs that ultimately warehouse and marginalize poor families and communities.” The committee also pledged to continue to advance an agenda “maximizing individual choice.”

One program they did like, however, was the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program. RAD permits public housing authorities to partner with local developers and nonprofit organizations to preserve public housing units that need rehab or other interventions so the affordable housing stock is not further depleted.

Housing developers are also watching another Trump proposal closely. With the administration’s proposed corporate tax cuts, the Low Income Housing Tax Credit could be less enticing, say housing experts. Investors are already cautious—just as rents saw the biggest annual jump since 2007.

“Trump hasn’t yet acted on his plan to slash the business tax rate from 35 percent to 15 percent, writes NextCity, “but the campaign pledge alone is already reshaping how affordable housing developers fund their work. The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) has financed millions of rental housing units that are affordable to low-income Americans, and the promise of lower corporate tax rates has reduced its value in the eyes of investors.

The National Low Income Housing Coalition sees peril ahead in other places, as it urges people to sign a letter to save the Housing Trust Fund. In addition, NLIHC notes, “Congress is considering reforms to the government sponsored enterprises (GSE), Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, in 2017. Because the HTF is funded through a small assessment on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s new business each year, reforms to the GSEs would have a direct impact on the HTF.”

What To Do to Preserve Affordable Housing?

Given these warning signs, housing experts are bracing for a changed landscape, likely with less government funding. With that in mind, a past article by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard might be worth another look. They outline three ways to build more affordable housing without subsidies in the Midwest, including building smaller homes, use factory-built homes, and creatively designed houses to get more out of them. Similarly, McKinsey Global Institute says the housing industry is long overdue for innovation and efficiencies in building. The construction industry’s labor productivity “is lower today than it was in 1968,” they write in “Reinventing Construction.” One option, say experts, is more off-site construction of housing, and McKinsey argues, better regulations, better design and engineering, more efficiencies, new materials, and a reskilled workforce, among others. (But then again, there’s always Soviet style, as this short animation reminds).

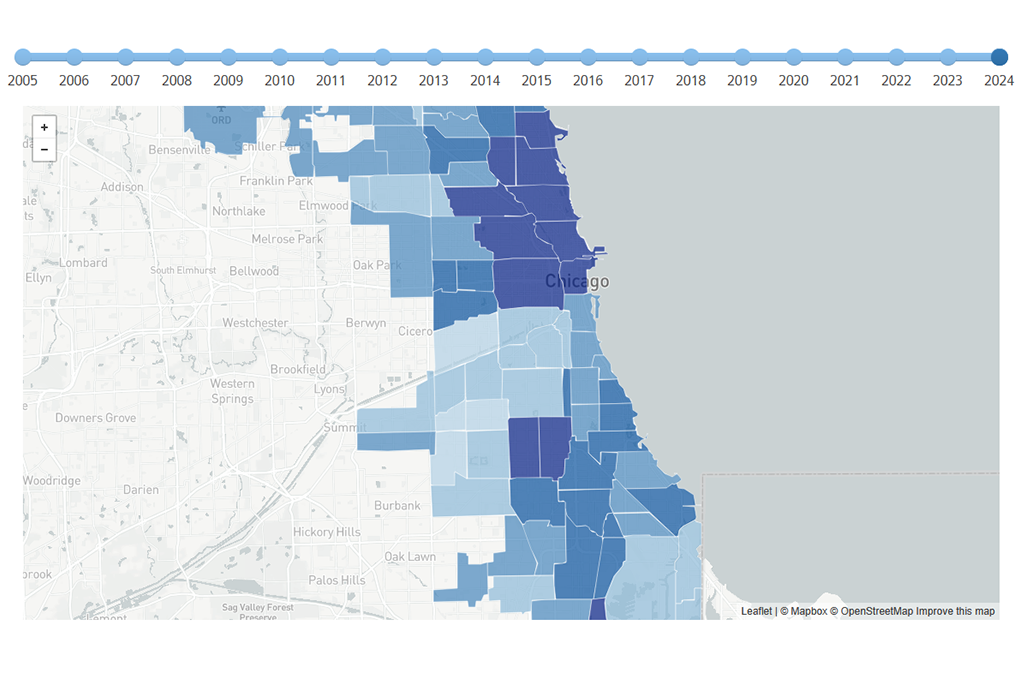

The Preservation Compact in Chicago and Cook County, whose mission is to preserve existing stock, which is much cheaper to maintain than to build new, has other solutions to encourage market rate owners to rehab their properties and keep rents affordable, including energy retrofits, property tax relief, and building code relief.

New sources of funding are emerging as well. Major hospital systems are beginning to focus their large endowments on building better housing in the neighborhoods they serve. As payment incentives push for more prevention, doctors are realizing that substandard housing is a major factor in many low-income children and families’ asthma, stress, and other costly conditions. Ohio’s Children’s Hospitals are at the vanguard. New equity funds are also beginning to invest in housing and communities in new ways. The National Housing Conference’s briefs have more on “housing as a platform” for economic and physical health.

Finally, a new regional and collaborative investment recently launched. The Strong, Prosperous, And Resilient Communities Challenge (SPARCC) is investing $90 million “to amplify locally driven efforts to ensure that major new infrastructure investments lead to equitable and healthy opportunities for everyone,” writes Enterprise, one of the partners in the endeavor.

Like most policy decisions today, the jury is still out on any final decisions. What isn’t changing any time soon is the need for much more affordable housing as Americans continue to struggle deal with volatile incomes, tight margins, and sagging wages.