As Chicagoans brace for a property tax increase to fill the city’s budget hole and the rising pressure of unfunded pensions, we sat down with the our executive director, Geoff Smith, to get his insights on which neighborhoods will feel the pain the most, and why.

IHS: It's official. Chicagoans will see their property taxes go up. But in focusing just on the new taxes, aren’t we overlooking another important factor that might mean an even bigger jump in taxes for some?

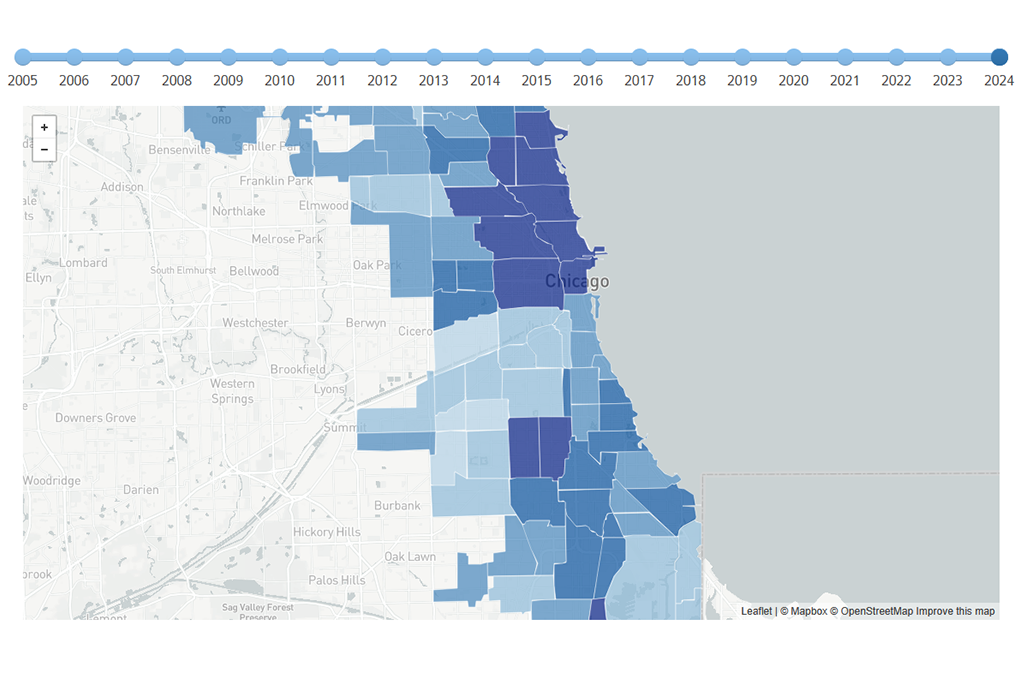

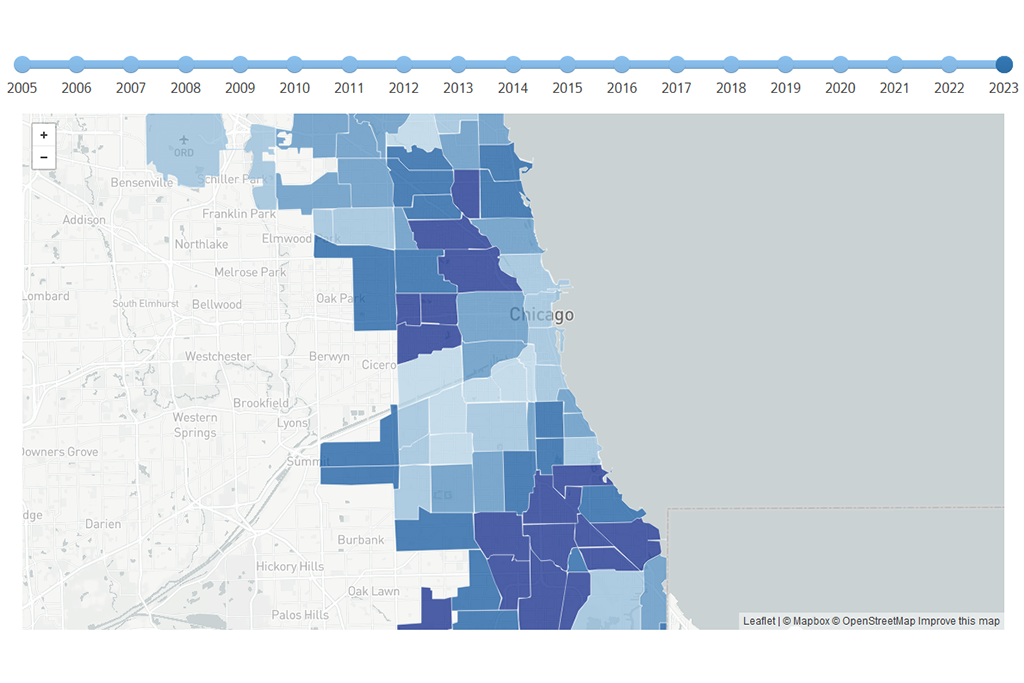

GS: Yes, a lot of focus is on the increased revenue that will be raised through property taxes. But most of the estimates out there on the potential impact of the tax increase are using a property’s current assessed values in their calculations. However, when the new taxes go into effect, they will be applied on new values that the Assessor’s Office is calculating this year as part of their triennial reassessment.

And that adds another level of complexity to the question of how this new tax increase will affect different neighborhoods.

IHS: So what’s the impact of the reassessment by itself, aside from the tax increase?

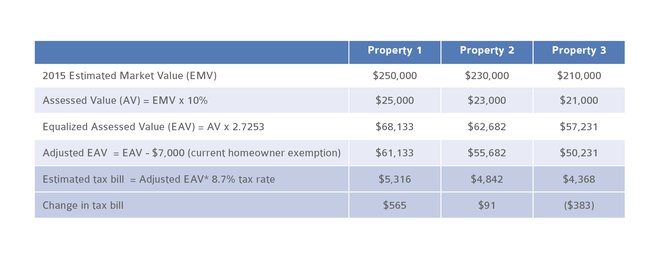

GS: Imagine three very similar owner-occupied, single-family properties in different neighborhoods in Chicago. In 2012, they each were valued at $200,000. Using a simple scenario, we would estimate that each would have a $4,751 property tax bill.

However, a lot has happened since 2012. Overall, the city’s housing market has made a recovery, but that recovery has been very uneven.

So let’s say that, citywide, property values increased, on average, by 15 percent since 2012. However, Property 1 is in a rebounding neighborhood that saw values increase by 25 percent, property 2 is an average neighborhood that saw values increase by 15 percent, and Property 3 is in a struggling neighborhood that saw values increase by only 5 percent.

As you can see in the table below, there’s quite a difference between the neighborhoods. The home in the struggling neighborhood would actually see a decline in property taxes. Remember, though, that this is before the new tax rate.

Property tax scenarios for three similar single-family homes in neighborhoods with differing price appreciation

Property tax scenarios for three similar single-family homes in neighborhoods with differing price appreciation

IHS: How are property taxes determined?

GS: Our colleagues at the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning have put together an easy to read guide explaining the property tax process. Essentially, the different taxing bodies—the City, County, schools, and park district—first determine how much they need to raise through property taxes to meet their budgets. This is the tax levy. The County then determines a tax rate based on that tax levy divided by the total adjusted equalized value of all properties in that taxing district, or the tax base.

In Chicago, the Cook County Assessor estimates a market value for every property, and then uses 10 percent of that value as the base amount to tax. They multiply that by an equalizer (now 2.7253). They then subtract any exemptions, like those for a homeowner or a senior. This final number is the adjusted equalized value of a property. The Assessor then applies the tax rate to that amount.

But as I said, one important wrinkle is that estimated market values for properties are reassessed every three years, and 2015 is the year for Chicago.

IHS: So which neighborhoods will be most affected by the reassessment?

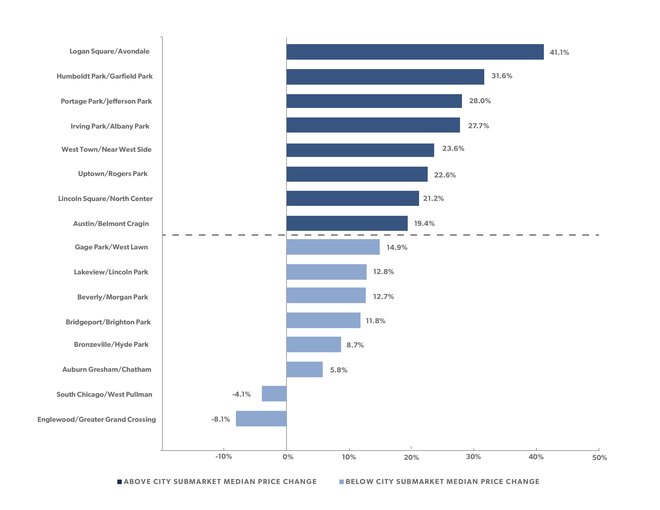

GS: Based on our price index, which allows us to estimate single-family price trends using sales data from 1997 on, the median neighborhood in Chicago saw properties increase in price between 2012 and 2014 by about 17 percent. Those areas above the median—largely on the city’s North and Northwest sides—are seeing more rapid increases in prices, and areas below the median—largely on the South and West sides—are seeing slower than average increases (or in some cases decreases) in prices. The figure shows the rate of increase for different neighborhoods.

Estimated price changes for single family homes by submarket in the City of Chicago, 2012 1Q to 2014 4Q

Estimated price changes for single family homes by submarket in the City of Chicago, 2012 1Q to 2014 4Q

So even before a tax increase, I would expect tax bills in an area like Logan Square/Avondale to increase because of the rapid rise in prices relative to the city average. Conversely, property tax bills may decline in areas like South Chicago/West Pullman or Auburn Gresham/Chatham due to slow price increases, or price decreases.

But—that’s a generalization. The assessor will value each property individually, and there may be properties in Logan Square with small increases and those in Chatham with substantial increases.

IHS: So this means taxes are going down in some neighborhoods?

GS: No. The property tax increase will affect all taxpayers in the city. Unless Springfield passes some type of increased homeowner exemption, the higher tax bill will offset any potential property tax decreases from being located in areas experiencing slow price appreciation. Additionally, even small increases in property taxes could hit families in these struggling neighborhoods harder because they have less ability to absorb additional housing costs.

IHS: Does this apply to multifamily rental properties and condo units, too?

GS: Our price index doesn’t track condos or rental buildings, but, generally speaking, yes. The uneven recovery in real estate values across neighborhoods will have an impact on the triennial reassessment and the taxes paid by different property types. Also, multifamily rental properties are not eligible for any proposed exemptions.

Our friends at the Preservation Compact have put together a nice summary of how property tax increases might affect affordable rental housing in Chicago. One of their concerns is that while rental building owners in stronger markets with growing demand will be able to pass the cost of any tax increases on to tenants via higher rents, owners in weaker markets might not be able to. So owners in these weaker areas will likely reduce operating costs somehow, maybe by deferring maintenance and investing less in rentals in these neighborhoods.

IHS: Bottom line?

GS: All property owners in Chicago will pay more in property taxes. It’s likely that rebounding neighborhoods will see bigger jumps in property tax changes compared to those areas that are still struggling, even without a rise in the exemption. And higher-priced homes and multifamily buildings will also foot the bill of any exemptions, should one be granted. That said, in those struggling areas, the real question is whether folks have the disposable income to absorb the increase.