Creative solutions to the housing affordability crisis are popping up all over the country. Micro-apartments—the Tiny Houses of apartment rentals—are at the forefront, but they aren’t the only ones. A Norwegian architect/engineer living in New York City is attaching apartment pods to the unused sides of tall buildings. A designer in London has created a pop-up apartment for use in abandoned buildings. A firm in Silicon Valley is 3D printing homes, in twelve hours.

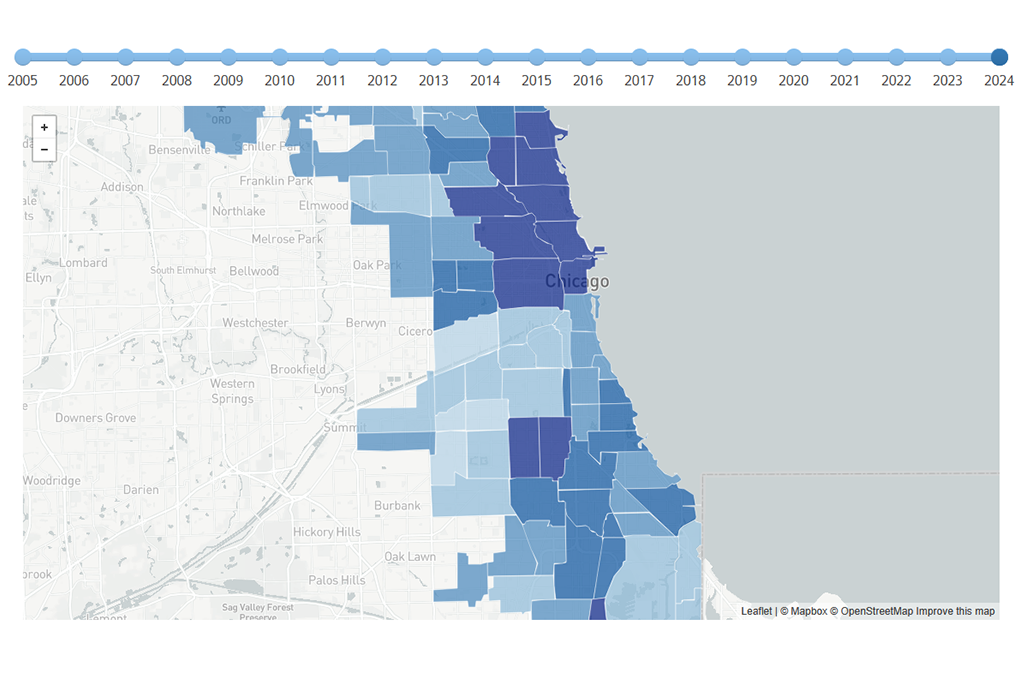

Creativity is certainly needed. The number of apartments deemed affordable for very low-income families fell by more than 60 percent between 2010 and 2016, according to Freddie Mac. In Chicago, the affordability gap—the difference between the number of affordable homes and those in need—has been on the rise, as we reported last month. The city’s supply of housing that is affordable has declined by more than 10 percent since 2012. In 2016 (the latest available data), the gap between available and needed affordable units stood at 119,000 units, the largest since at least 2012.

But while tiny apartments and other innovations are marketed as one answer to affordability problems, not everyone is convinced.

The Rise of the Tiny Apartment

Cities across the country from Berkeley to Boston are loosening density and size restrictions and building micro-units, apartments typically around 350 square feet or less. These tiny apartments have been called the “new model for the development of affordable housing.”

New York City was an early adopter with its Carmel Place, which recently won the HIVE (housing, innovation, vision, and economics) award for design and is considered a benchmark for future micro-housing initiatives. Nearly half the units have below-market rents for low-income individuals.

In the rapidly gentrifying Logan Square neighborhood in Chicago, a planned development was recently upzoned for 138 micro-apartments. Rents are about $1200-1400, which is the average cost for a one-bedroom in Logan Square, according to Domu. In addition, the project has set aside 20 units as affordable.

Developers love micro-units because they can build more and charge more per square foot than larger apartments. Many are marketed to a new consumer, who is ditching materialism for a streamlined lifestyle. Small units, says Jeff Wilson, founder of Kasita, are “built not for a demographic but for a psychographic, for people who want to live lightly.” Or as the 2016 World Economic Forum put it: “Welcome to 2030. I own nothing, have no privacy, and life has never been better.”

Designers Get Creative

Others see micro-units as a remedy for homelessness. That was the case for Norwegian architect Andreas Tjeldflaat. While riding the New York City subway, he struck up a conversation with a homeless man, who told him he hated shelters because they were unsafe. Tjeldflaat knew the hurdle in building affordable housing was the high cost of land. But why not re-imagine what “land” is, he thought. Why not attach micro-units to the blank side of a building.

His HOMED solution –still in the concept phase—is a marvel of innovation. Hexagonal modules large enough for a small bed, chair, and storage are constructed off-site and attached to exposed sides of buildings, like barnacles but pretty. The housing modules essentially create “suspended micro-neighborhoods of shelters.”

Image: FramLab

Image: FramLab

Also constructed off-site, MicroPad is one answer to San Francisco’s homeless population. The apartments can be assembled like Legos on unused land or land with little value, which cuts costs by 40 percent according to the builder’s website.

Others bypass construction altogether and have a 3D printer do it. A printer squirts out the home in less than a day. For $4,000. LA homeowners who want to join in on the YIMBY movement might want to take note.

Other prefab advances are cutting costs. With the lightweight BONE Structure system, builders laser cut a home’s columns and beams in a manufacturing plant and a five-person crew assemble the shell in days on site, Ikea-like, using only battery-powered drills and self-tapping screws.

And in London, squatting is going upscale. There, squatters, aka “guardians,” are paid to keep an eye on a building that is abandoned and awaiting redevelopment. One guardian decided to improve the often awful conditions and created Shed, a kind of pop-up apartment that the guardians can construct themselves. Rents run about 50 percent below market rates.

But Not Everyone is Enamored

The innovations are welcome in an era of rising unaffordability. But tiny homes are not a silver bullet by any means, say advocates. Micro-units overlook the needs of larger households and might displace larger apartments. Others argue that the micro-units are simply a return to the cramped conditions of eras past.

Some cities are dubious. Hoping to encourage developers to build larger units for families, Santa Monica recently passed a law that limits micro-units to 15-20 percent of a building. Denver recently put a moratorium on micro-unit developments on tiny lots with no off-street parking. Seattle, where micro-units accounted for nearly one-quarter of the city’s housing growth in 2013, heavily regulated them, which one analyst says has led rents to rise by $300.

Building codes are another hurdle, and their complexity creates a challenge for affordability. Micro-units must conform to codes that govern density, parking requirements, floor area ratio, and other approved uses, not to mention complicated zoning issues. “In large cities, it’s not uncommon for clients to hire a consultant, such as a land use attorney, to navigate zoning resolutions,” said Murray Bernard in Architecture Magazine.

Whether they are the answer, or even an answer, to the affordable housing crisis is debatable. The Brookings Institute’s Alan Berube is not convinced. “More supply is better, but we shouldn’t kid ourselves that micro-apartments alleviate the burdens low-income renters are facing,” he told the New Yorker. As Berube alludes, micro-units are an option in strong housing markets to add supply. But in neighborhoods or communities where housing is unaffordable because incomes are low or declining, supply is not the issue. In those neighborhoods, low-cost apartments abound, but neighborhood residents still cannot afford them because their incomes are too low.

In fact, Chicago is losing a type of micro-unit that truly is affordable to low-income individuals, the single-room occupancy hotel. Since 2014, the number of licensed SRO buildings in the City of Chicago dropped from 81 to 66. In many cases, long-time SROs that are in significant need of updating are being upgraded to apartments that will no longer be affordable to former tenants.

Micro-units are adding more units to the market and building more densely on expensive land. But they are not yet a panacea to the affordability crisis. They are a literal drop in the bucket compared with need.