This is the second in a series of posts discussing long-term residential vacancy in Chicago and suburban Cook County. For the first post in this series, click here.

The first post in this series, Understanding vacancy: Patterns of long-term vacancy in Cook County, discussed why a residential address may become vacant and how properties that remain vacant over a long period of time are more likely to contribute to blight. Cook County’s long-term vacant addresses are concentrated in a set of highly foreclosure-distressed census tracts and research shows that in neighborhoods that already have high levels of long-term vacancy, new properties entering foreclosure are more likely to become vacant and abandoned.

It is in these areas with high levels of long-term residential vacancy, a sign of low demand and a weak housing market, where public policy interventions that address residential abandonment and vacancy are most needed and can be most difficult to apply.

In this post we’ll discuss one policy tool, Illinois Senate Bill 16, intended to help stop the cycle of foreclosed residences from contributing to the stock of blighted, vacant properties. A key provision of the new law, set to take effect in June, is to fast-track the mortgage foreclosure process for homes that have been determined to have been abandoned by their owners.

In addition to fast-tracking, Senate Bill 16 applies multiple approaches to the problem of foreclosure-related, long-term residential vacancy. The law’s key provisions include:

- Requiring financial institutions to pay an additional fee for each new foreclosure they file

- Giving both the local municipality and mortgage-holding institution the legal right to physically secure and maintain abandon properties in the foreclosure process

- Shortening the foreclosure process for an abandoned property to as little as 90 days

The fast-tracking of vacant properties through the foreclosure process is important because, in Illinois, foreclosures are carried out through the court system which is bottlenecked with foreclosure proceedings as a result of the housing crisis and a back log of cases that built up during the robosigning scandal. In Illinois, the approximate time a foreclosure can be completed in 12-15 months. However, it took banks in Illinois an average of 697 days to repossess a home as of the fourth quarter of 2012. While the number of homes entering foreclosure is down nationwide since its peak in 2010, Illinois had the third highest foreclosure rate in the country as of March 2013 and is still working through its backlog of filings.

Though the new law somewhat mitigates this legal murkiness by providing a path for financial institutions to fast-track a home through foreclosure in as little as 90 days, it cannot guarantee the courts ability to expedite the process, and the law requires that the fast-tracking come to a halt if the property owner re-emerges. According to a recent examination of the new law in Crain’s Chicago Business, banks are likely to approach fast-tracking cautiously in part for these reasons.

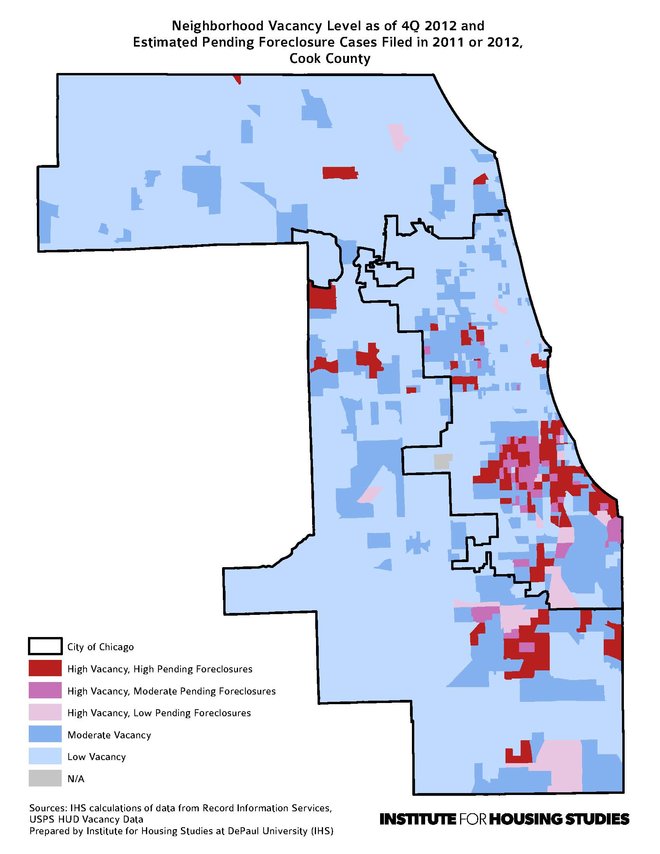

The map below shows areas in Cook County with high levels of long-term vacancy and high levels of pending foreclosures in red. These areas represent another challenge to the law’s efficacy in addressing long-term vacancy. Neighborhoods with both high levels of long-term residential vacancy and a large amount of pending foreclosures are those where properties stuck in the foreclosure process are most likely to be vacant and at the highest risk of becoming blighted. The map shows that these high-risk areas are concentrated on the City’s South and West sides and in south suburban Cook County. These areas are likely the ones that would benefit the most from fast-tracking vacant properties through the foreclosure process. However, financial institutions may have little incentive to fast-track vacant homes in these areas because of a lack of demand and limited options for quick disposition. One possible outcome is that the fast-tracking provision of the new law will be utilized, but largely in stronger markets where banks have more certainty that they can re-sell the property.

Map showing vacancy level in Cook County as of 4Q 2012 and estimated pending foreclosures filed in 2011 and 2012

Map showing vacancy level in Cook County as of 4Q 2012 and estimated pending foreclosures filed in 2011 and 2012

While the new fast-tracking law represents a potentially powerful tool for local governments and banks to secure abandoned homes and to bring those homes to foreclosure auction faster, it is only applicable to properties that are still in the foreclosure process and may be underutilized by banks, particularly for homes in the weakest markets.

The final post in this series will discuss the newly formed Cook County Land Bank Authority, whose purpose is to secure long-term vacant properties for eventual redevelopment.

To be notified about new blog posts and to provide feedback, follow us on twitter, like us on Facebook, or join our LinkedIn Group.