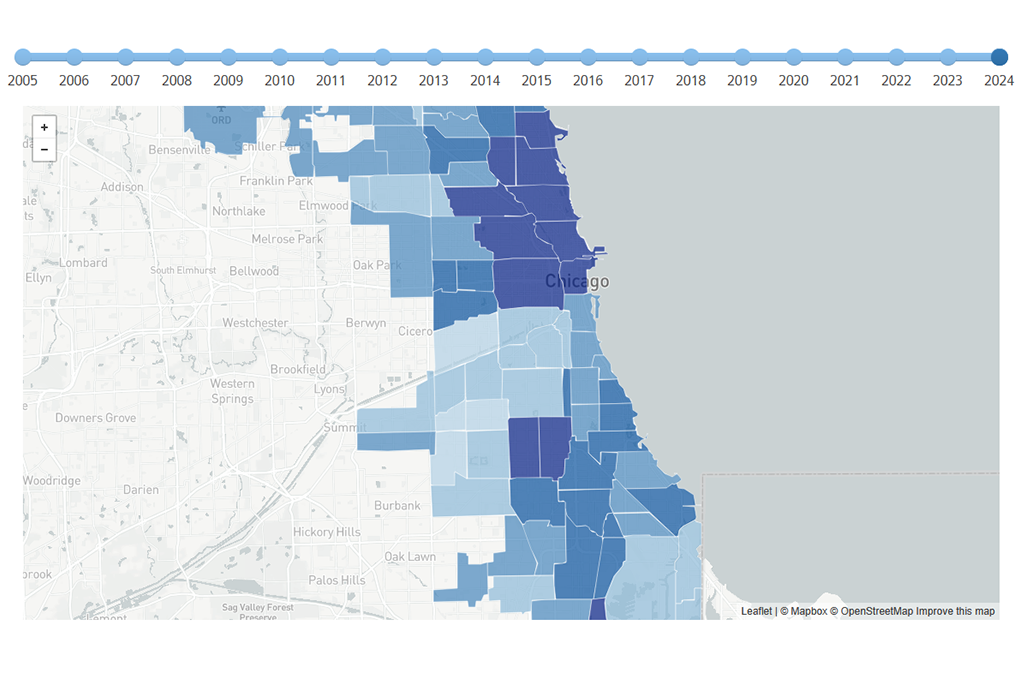

How a unique partnership between organizers and data analysts helped a community group on Chicago’s southwest side develop strategies to stabilize the neighborhood’s housing market.

In August, Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan took a walking tour of the Chicago Lawn neighborhood. She was there to review the progress in a neighborhood that had been hard hit by the foreclosure crisis and accordingly received some of the National Foreclosure Settlement funds Madigan has secured. The money is being used to rehab vacant properties and stabilize the neighborhood.

The Southwest Organizing Project (SWOP) is overseeing the process and worked with the Institute for Housing Studies to use data to help refine their strategy and make sense of what they believed was going on in the neighborhood. What they learned surprised them.

The community group has long been engaged in a campaign to address foreclosure, vacancy, and predatory lending in Chicago Lawn. A few years ago, organizers from SWOP rounded up some clipboards and pencils and hit the surrounding streets to map every vacant home in the three square-mile area. The unoccupied properties were a great cause of concern for the organizers, who knew that each month a home sat empty it lost value. SWOP was concerned that, as was the case in adjacent neighborhoods, far-flung institutional investors were scooping up these properties, which raised questions about the ownership practices of these new landlords.

Every member of Chicago Lawn’s diverse community—residents, educators, religious leaders—knew a family who had lost its home during the crisis. These stories inspired sympathy but did not always motivate organized action as SWOP wished they would. It was challenging to get a sense of how an individual’s experiences fit into the greater neighborhood context, and how the neighborhood fit into regional or national trends. The vacant properties clearly affected individuals and families, but SWOP wanted to show people how they affected the neighborhood as a whole.

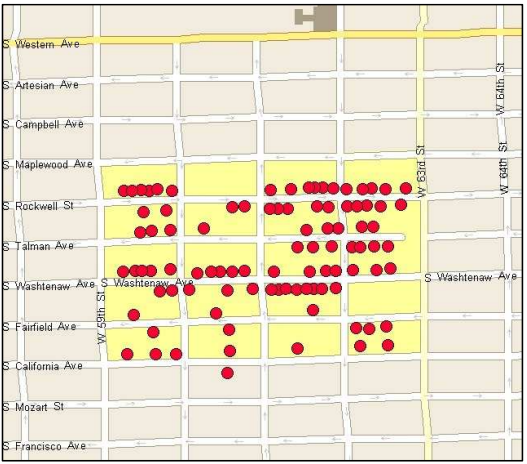

The organizers began making paper maps of the data they gathered on their walks. The maps, pocked with red dots representing vacant homes, revealed that the problem was widespread and structural.

Vacant Properties in SWOP Target Area 2012. Map: SWOP

Vacant Properties in SWOP Target Area 2012. Map: SWOP

SWOP had had success using maps as an organizing tool in the past, according to Senior Organizer David McDowell. McDowell said that seeing the effects of foreclosures on their neighborhood—displayed block by block— helped residents and community leaders better understand the scope of the crisis. In 2008, when organizers showed a local pastor a map of local foreclosures, for example, he was stunned.

“His response was, ‘Wow. If this had been a tornado that had swept through my parish and impacted this many families, my parishioners would have an instantaneous and visceral response. They’d show up,’” McDowell said.

This time, SWOP organizers wanted to use maps again as part of their plan to acquire and rehab as many of the neighborhood’s vacant homes. But there was only so much the group could do with the information they had. Their earlier survey findings didn’t answer some of their most pressing questions: Were these properties in fact being purchased? By whom?

“We wanted to look at a deeper level about how [vacancies were] impacting the neighborhood,” McDowell said.

SWOP turned to the Institute for Housing Studies (IHS) for help. A research center based at DePaul University, the institute focuses on affordable housing and conducts research on the changing dynamics of neighborhood housing markets. Analysts at IHS regularly partner with community organizations to help them access and gather data that can help them to make informed choices and policy decisions.

SWOP has a longstanding relationship with IHS. IHS often provides technical assistance to SWOP, producing a wide variety of deliverables on an ad-hoc basis from pulling data points to support a grant application to creating maps of mortgage activity in the Chicago Lawn community. Between 2012 and 2015, IHS was funded to be SWOP’s data intermediary, building the organizations data capacity as part of LISC Chicago’s Testing the Model program. The vacancy project was part of this work.

IHS was able to blend SWOP’s vacant building survey data with administrative data from county agencies, producing a more detailed analysis of Chicago Lawn’s vacant housing stock. The IHS staff combined SWOP’s findings with transaction, mortgage and foreclosure information. That helped them determine which properties had sold and when, and figure out the typical buyer profile.

One of the findings was especially surprising. The vacant properties were frequently being purchased by private individuals—not institutional investors, as SWOP has suspected. For SWOP, the revelation was critical.

“As a small community organization, our resources are limited,” McDowell said. “We need to make sure we only address actual threats.” SWOP used this new information to shift its focus away from institutional investors.

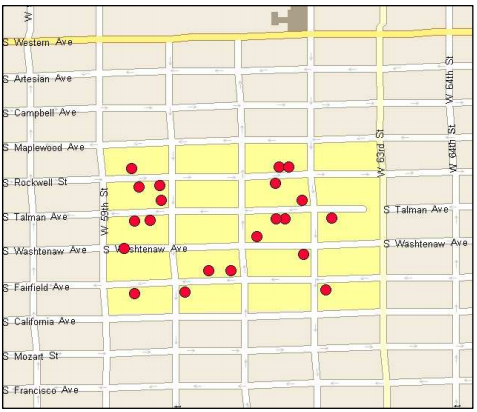

Vacant Properties in SWOP Target Area 2016. Map: SWOP

Vacant Properties in SWOP Target Area 2016. Map: SWOP

McDowell said that the partnership with IHS helped SWOP gain important insights, and better understand the data they had in front of them. For example, organizers learned what they could truthfully say based on the information they had. They learned when a sample size is too small and when data are too old.

That gave the group confidence that they were presenting the most accurate information in their organizing efforts.

The benefit of the partnership has been mutual. Partnerships and technical assistance work are vital components of IHS’s applied research model. This project deepened IHS staff’s understanding of the kinds of questions community based organizations have, how they use data, and how these may be different from the data lobbyists and policymakers look for. SWOP also brings trust and deep knowledge of the Chicago Lawn community— assets that were key to understanding the results of IHS’s analysis and the overall success of the effort.

The established relationship between SWOP and IHS was critical to the success, McDowell said. SWOP knew IHS was dedicated to exploring the organizers’ questions—and, on their part, they trusted the analysts when they explained that certain information was impossible to gather or dissect.

This relationship, built on mutual respect and trust, helped the project avoid mistakes commonly made in partnerships between researchers and community groups.

“Community-based organizations increasingly need data to ground the stories they are hearing from constituents in some type of empirical evidence,” says Smith. “However working with data can be very complicated and require a specific skill set. Many organizations lack the resources to have dedicated staff trained in data analysis. That makes the role of data intermediaries like IHS all the more critical.”

IHS’s applied research model equipped the SWOP organizers with a deeper understanding of their community and evidence they could use to help organize for change.

And their work had results. SWOP’s campaign to acquire and rehab homes in Chicago Lawn has reduced the vacant housing stock from 93 properties to 21. The red dots on those original maps are growing more rare—and the groups are working to get rid of them altogether.

Photo/Google Maps